The Victorians

Excerpt from Samuel Butler's 'The Way of all Flesh'

Go back to The Butlers. Go back to The Victorians.

Samuel Butler wrote his most famous book between 1873 and 1884, but he did not want it published during his lifetime. He died in 1902 and the book was published in 1903.

It is a work of fiction telling the story of a family in Victorian England. It is a work of fiction but many of the things that happen to the hero also happened to Samuel Butler. The hero is the son of a bullying priest; he leaves home and makes his own way in the world - just like Samuel Butler did. This novel was Butler's way of criticising Victorian Britain - and his own family.

Samuel Butler describes a village in 'The Way of all Flesh' which he calls Battersby on the Hill - it is a good description of Langar in the first half of the 19th century.

Notes:

In the novel Samuel Butler models the Pontifex family on his own family. Theobald Pontifex, the Rector of Battersby on the Hill, is like his own father; Christina Pontifex is like his own mother; and the son, Ernest is like Samuel Butler himself. The story is told by Edward Overton, Ernest's godfather and a friend of Theobald.

This chapter describes Battersby church and the village people in 1834 when Theobald arrived to be Rector - this was the year Samuel Butler's own father came to Langar. Theobald then rebuilds the church, as his father did, and the chapter describes the changes to the church and people.

This is not an easy piece - it is written for adults and written in Victorian English and it assumes you know a lot about Victorian England. After the chapter there are some helpful notes further down this page.

Chapter XIV

Edited

Battersby-On-The-Hill was the name of the village of which Theobald was now Rector. It contained 400 or 500 inhabitants, scattered over a rather large area, and consisting entirely of farmers and agricultural labourers. The Rectory was commodious, and placed on the brow of a hill which gave it a delightful prospect. There was a fair sprinkling of neighbours within visiting range, but with one or two exceptions they were the clergymen and clergymen’s families of the surrounding villages.

By these the Pontifexes were welcomed as great acquisitions to the neighbourhood. Mr Pontifex, they said was so clever; he had been senior classic and senior wrangler; a perfect genius in fact, and yet with so much sound practical common sense as well. Of course they would give dinner parties.

And Mrs Pontifex, what a charming woman she was; she was certainly not exactly pretty perhaps, but then she had such a sweet smile and her manner was so bright and winning. She was so devoted too to her husband and her husband to her; it was rare to meet with such a pair in these degenerate times; it was quite beautiful, etc., etc. Such were the comments of the neighbours on the new arrivals.

As for Theobald’s own parishioners, the farmers were civil and the labourers and their wives obsequious. There was a little dissent, the legacy of a careless predecessor, but as Mrs Theobald said proudly, “I think Theobald may be trusted to deal with that.”

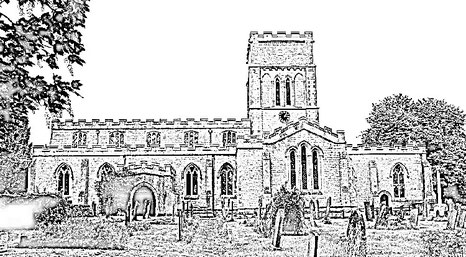

The church was then an interesting specimen of late Norman, with some early English additions. It was what in these days would be called in a very bad state of repair, but forty or fifty years ago few churches were in good repair. If there is one feature more characteristic of the present generation than another it is that it has been a great restorer of churches.

I may say here that before Theobald had been many years at Battersby he found scope for useful work in the rebuilding of Battersby church, which he carried out at considerable cost, towards which he subscribed liberally himself. He was his own architect, and this saved expense; but architecture was not very well understood about the year 1834, when Theobald commenced operations, and the result is not as satisfactory as it would have been if he had waited a few years longer.

I remember staying with Theobald some six or seven months after he was married, and while the old church was still standing. I went to church and I have carried away a more vivid recollection of this and of the people, than of Theobald’s sermon.

Even now I can see the men in blue smock frocks reaching to their heels, and more than one old woman in a scarlet cloak; the row of stolid, dull, vacant plough-boys, ungainly in build, uncomely in face, lifeless, apathetic, a race a good deal more like the pre-revolution French peasant, a race now supplanted by a smarter, comelier and more hopeful generation, which has discovered that it too has a right to as much happiness as it can get, and with clearer ideas about the best means of getting it.

They shamble in one after another, with steaming breath, for it is winter, and loud clattering of hob-nailed boots; they beat the snow from off them as they enter, and through the opened door I catch a momentary glimpse of a dreary leaden sky and snow-clad tombstones.

They bow to Theobald as they passed the reading desk (“The people hereabouts are truly respectful,” whispered Christina to me, “they know their betters.”), and take their seats in a long row against the wall.

The choir clamber up into the gallery with their instruments — a violoncello, a clarinet and a trombone. I see them and soon I hear them, for there is a hymn before the service, a wild strain.

Gone now are the clarinet, the violoncello and the trombone. Gone is the bellowing bull, the village blacksmith, gone is the melodious carpenter, gone the brawny shepherd with the red hair, who roared more lustily than all, until they came to the words, “Shepherds with your flocks abiding,” when modesty covered him with confusion, and compelled him to be silent, as though his own health were being drunk. They were doomed and had a presentiment of evil, even when first I saw them, but they had still a little lease of choir life remaining, and they roared out: 'wick-ed hands have pierced and nailed him, pierced and nailed him to a tree.'

When I was last in Battersby church there was a harmonium played by a sweet-looking girl with a choir of school children around her, and they chanted the canticles to the most correct of chants, and they sang 'Hymns Ancient and Modern'; the high pews were gone, nay, the very gallery in which the old choir had sung was removed, and Theobald was old, and Christina was lying under the yew trees in the churchyard.

But in the evening later on I saw three very old men come chuckling out of a dissenting chapel, and surely enough they were my old friends the blacksmith, the carpenter and the shepherd. There was a look of content upon their faces which made me feel certain they had been singing; not doubtless with the old glory of the violoncello, the clarinet and the trombone, but still songs of Sion and no new fangled papistry.

Chapter XIV - some explanations

Edited and annotated

Battersby-On-The-Hill was the name of the village of which Theobald was now Rector. It contained 400 or 500 inhabitants, scattered over a rather large area, and consisting entirely of farmers and agricultural labourers. The Rectory was commodious, and placed on the brow of a hill which gave it a delightful prospect. There was a fair sprinkling of neighbours within visiting range, but with one or two exceptions they were the clergymen and clergymen’s families of the surrounding villages.

- This is an accurate description of Langar and the Rectory at the time.

- 'Commodious' means large and spacious. 'Prospect' - a good view.

- 'Neighbours' - this does not mean people who lived close by; it means nice middle class people that the Rector and his family could visit to take afternoon tea. They weren't many - mostly they were clergy (priests, vicars and rectors).

By these (neighbours) the Pontifexes were welcomed as great acquisitions to the neighbourhood. Mr Pontifex, they said was so clever; he had been senior classic and senior wrangler; a perfect genius in fact, and yet with so much sound practical common sense as well. Of course they would give dinner parties.

And Mrs Pontifex, what a charming woman she was; she was certainly not exactly pretty perhaps, but then she had such a sweet smile and her manner was so bright and winning. She was so devoted too to her husband and her husband to her; it was rare to meet with such a pair in these degenerate times; it was quite beautiful, etc., etc. Such were the comments of the neighbours on the new arrivals.

- 'Senior classic', 'senior wrangler' - Top of the class at Cambridge University in Classics (Latin and Greek) and mathematics. Samuel Butler, his father and grandfather were all brilliant students but not senior wranglers.

- 'These degenerate times' - things are getting worse and worse nowadays.

As for Theobald’s own parishioners, the farmers were civil and the labourers and their wives obsequious. There was a little dissent, the legacy of a careless predecessor, but as Mrs Theobald said proudly, “I think Theobald may be trusted to deal with that.”

- 'Civil' - polite. 'Obsequious' - keen to please, agree, obey.

- 'There was a little dissent, the legacy of a careless predecessor' - During the 19th century many ordinary people failed to connect with the Church of England. Services were authoritarian, unenthusiastic and boring; the Church was seen as part of the Establishment, the rich and powerful who rule the land. A number of break-away churches were formed - a Methodist church was built on Main Road at Barnstone. The 'careless predecessor', the Rector before Theobald, must have allowed his congregation to discuss such matters - but Mrs Pontifex was sure her husband would stamp out such nonsense.

The church was then an interesting specimen of late Norman, with some early English additions. It was what in these days would be called in a very bad state of repair, but forty or fifty years ago few churches were in good repair. If there is one feature more characteristic of the present generation than another it is that it has been a great restorer of churches.

- By the end of the 19th century, people appreciated the mixture of historical styles in old churches. 'Norman with early English'. It is true that during the 18th century the condition of church buildings had begun to deteriorate - badly in some cases.

I may say here that before Theobald had been many years at Battersby, he found scope for useful work in the rebuilding of Battersby church, which he carried out at considerable cost, towards which he subscribed liberally himself. He was his own architect, and this saved expense; but architecture was not very well understood about the year 1834, when Theobald commenced operations, and the result is not as satisfactory as it would have been if he had waited a few years longer.

- Rebuilding Battersby church largely at his own expense - this is what Samuel Butler's father did to St Andrew's church, Langar.

- 'If he had waited a few years longer' - Views on old church architecture changed during the Victorian period. In the middle years of the 19th century, people wanted to restore churches back to how they thought they should have looked in the Middle Ages - they didn't always get it right and sometimes destroyed original medieval architecture. Later in the 19th century, people were more careful to keep as much of the old church building as possible and just repair what was necessary. Samuel Butler's father made some radical changes to Langar church - he covered the building in new stone, he rebuilt the windows and altered the tower.

I remember staying with Theobald some six or seven months after he was married, and while the old church was still standing. I went to church and I have carried away a more vivid recollection of this and of the people, than of Theobald’s sermon.

Even now I can see the men in blue smock frocks reaching to their heels, and more than one old woman in a scarlet cloak; the row of stolid, dull, vacant plough-boys, ungainly in build, uncomely in face, lifeless, apathetic, a race a good deal more like the pre-revolution French peasant, a race now supplanted by a smarter, comelier and more hopeful generation, which has discovered that it too has a right to as much happiness as it can get, and with clearer ideas about the best means of getting it.

- The writer says that in 1834, farm workers were 'apathetic' - they had a hard life, but they just put up with it. Now, he says, farm workers are 'smarter', 'more hopeful' and believe they have a right to happiness. Education may have had something to do with this. In 1834 many ordinary people were illiterate; in 1842 Rev Thomas Butler opened the church school at Langar and children learned to read and write.

They shamble in one after another, with steaming breath, for it is winter, and loud clattering of hob-nailed boots; they beat the snow from off them as they enter, and through the opened door I catch a momentary glimpse of a dreary leaden sky and snow-clad tombstones.

They bow to Theobald as they passed the reading desk (“The people hereabouts are truly respectful,” whispered Christina to me, “they know their betters.”), and take their seats in a long row against the wall.

The choir clamber up into the gallery with their instruments — a violoncello, a clarinet and a trombone. I see them and soon I hear them, for there is a hymn before the service, a wild strain.

- In medieval churches there was often a gallery up above the chancel arch - the arch dividing the nave of the church where the people sat and the chancel at the front of the church where the priest celebrated Holy Communion. Before church organs became popular, the village band sat up in the gallery to play the music for the hymns.

Gone now are the clarinet, the violoncello and the trombone. Gone is the bellowing bull, the village blacksmith, gone is the melodious carpenter, gone the brawny shepherd with the red hair, who roared more lustily than all, until they came to the words, “Shepherds with your flocks abiding,” when modesty covered him with confusion, and compelled him to be silent, as though his own health were being drunk. They were doomed and had a presentiment of evil, even when first I saw them, but they had still a little lease of choir life remaining, and they roared out: 'wick-ed hands have pierced and nailed him, pierced and nailed him to a tree.'

-

By the end of the 19th century the galleries had been taken out and replaced with harmoniums (simple

wind-powered organ). Rectors felt that the village band was not proper for church - after all, this was the same band that played at the village pub for May Day dances and suchlike.

Rectors were glad to have more control. The organ at Langar came from Codnor church in Derbyshire (They had bought a bigger one). It was installed in 1906.

When I was last in Battersby church there was a harmonium played by a sweet-looking girl with a choir of school children around her, and they chanted the canticles to the most correct of chants, and they sang 'Hymns Ancient and Modern'; the high pews were gone, nay, the very gallery in which the old choir had sung was removed, and Theobald was old, and Christina was lying under the yew trees in the churchyard.

- The 'girl' playing the harmonium would have been the village schoolmistress and the choir were from the village school.

-

'Hymns Ancient and Modern' was a hymn book of 1861 with a collection of hymns suitable for Church of England

churches.

- 18th century churches had high pews, like boxes. Wealthier people had their own pews; poorer people sat on benches at the back.

- Very few churches now have a gallery - they were almost all taken out by the end of the 19th century.

But in the evening later on I saw three very old men come chuckling out of a dissenting chapel, and surely enough they were my old friends the blacksmith, the carpenter and the shepherd. There was a look of content upon their faces which made me feel certain they had been singing; not doubtless with the old glory of the violoncello, the clarinet and the trombone, but still songs of Sion and no new fangled papistry.

-

'The dissenting chapel' - this would be a Methodist where the ordinary folk of the village felt more comfortable: the service was less

formal, the hymns were loud and jolly; the minister (priest) was not a wealthy clever man like the Rector and they did not have to sit at the back of the church behind the lord of the

manor and the other rich people of the parish.

A Methodist church was built just outside Barnstone in the middle of the 19th century, just when Rev Thomas Butler was making all the changes to St Andrew's, Langar. (It closed in 1977 but the building still there on Main Road.) In 1856 the lord of the manor rebuilt the tumble-down St Mary's Barnstone, almost certainly in competition with the Methodist chapel. - 'New-fangled papistry' - While the Methodist church was becoming less formal, many Church of England priests were making their services more formal, going back to the style of Services in the Middle Ages when England was Roman Catholic. The words 'papistry' comes from the word 'Pope', the leader of the Roman Catholic church.

Want to know more about the changes at Langar church? Click!