The 19th Century

and the Reign of Queen Victoria

1837 - 1901 - largely the 1800s (19th century)

START: Victoria became queen in 1837 at the age of 18.

END: She died in 1901 after being queen for 63 years, the longest reign of any monarch up to then.

See also Victorian Lords of the Manor, The Butler Family, Langar School and the Coming of the Railways.

Langar and Barnstone - two farming villages in the Vale of Belvoir

For 10,000 years people have lived and worked at Langar and Barnstone farming the land. They have kept animals and grown crops to feed themselves and the nation.

Slump, depression - then

the Golden Age of English Farming

But first - the end of the Georgian era -

The Battle of Trafalgar 1805 The battle of Waterloo 1815

The 19th century began with war against the French emperor Napoleon who planned to invade Britain. (George III was king at the time.) The French navy was defeated at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 by the British fleet under the command of Admiral Lord Nelson; Napoleon's army was finally defeated by the British led by the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Peace should have led to a time of stability and prosperity - but that did not happen.

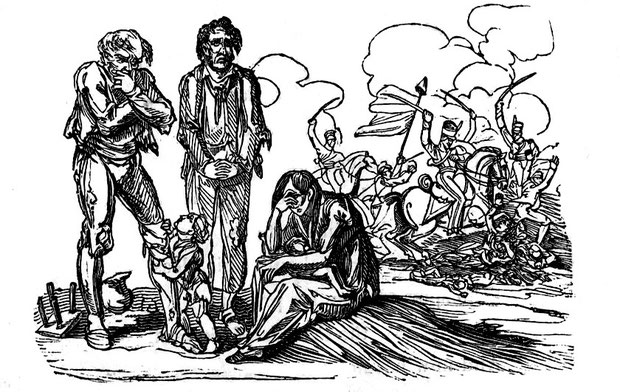

Slump

After the wars with Napoleon, there was a slump in British industry and agriculture.

Although prices fell, many people had no jobs and no money. And low prices were not good for farmers or industrialists who got less money for their products.

Only one year after the war, the value of some farms in Nottinghamshire had fallen by half. The price that farmers got for their wheat fell to a third of what it had been.

The depression lasted for 20 years.

However, some farmers in the Vale of Belvoir did well. Farmers with light sandy land who farmed in the 'modern' way, who worked 4-course rotations, who grew wheat, who grew turnips and fattened sheep and bullocks, increased their production and their income.

(See The Georgians for innovations in farming.)

But farmers in the Vale of Belvoir who grew wheat on heavy clay soil did badly. They had been used to growing wheat on difficult land because it had fetched a high price. But they farmed in the old-fashioned way leaving a fallow field every year with no crops. Now the price they got for their wheat had dropped, wheat was not worth growing. In the Vale of Belvoir, growing wheat on heavy clay soils stopped altogether.

Langar & Barnstone - up for sale!

Langar and Barnstone had been the property of members of the Howe family who were lords of the manor. They owned the hall and most of the land. But by the end of the 18th century they hardly ever came to Langar Hall.

(See Georgian Lords of the Manor if you want to know more.)

In 1818 Baroness Sophia Charlotte Howe sold all her property at Langar to John Wright of Lenton Hall, Nottingham. John Wright was a millionaire industrialist who owned the Butterley Company in Derbyshire. The company produced iron and was very successful during the wars with France producing iron to make into cannons and guns.

John Wright bought Langar at a bargain price.

Baroness Howe wanted to sell Langar and farming was not doing well. John Wright became the owner of Langar Hall and all the land in Langar and Barnstone, about 4000 acres, except for three farms at Barnstone and 400 acres of glebe lands belonging to the church. And he also became the lord of the manor.

(See Victorian Lords of the Manor if you want to know more.)

The Golden Age of Farming - new inventions

The problem for farmers with heavy clay is that it becomes waterlogged when it rains. Crops rot in very wet soil. In 1826 the government removed the tax on drainage tiles to make them cheaper. Drainage tiles are underground pipes to drain water away.

In 1845 Thomas Scragg invented a machine to make clay drainpipes. It was operated by just one man and three boys, who could make 11,000 tiles a day. Many farmers laid drains and farming on clay land soon began to catch up with the farms on lighter sandy land. In Nottinghamshire and across England, agriculture improved steadily and moved into

the Golden Age of English farming.

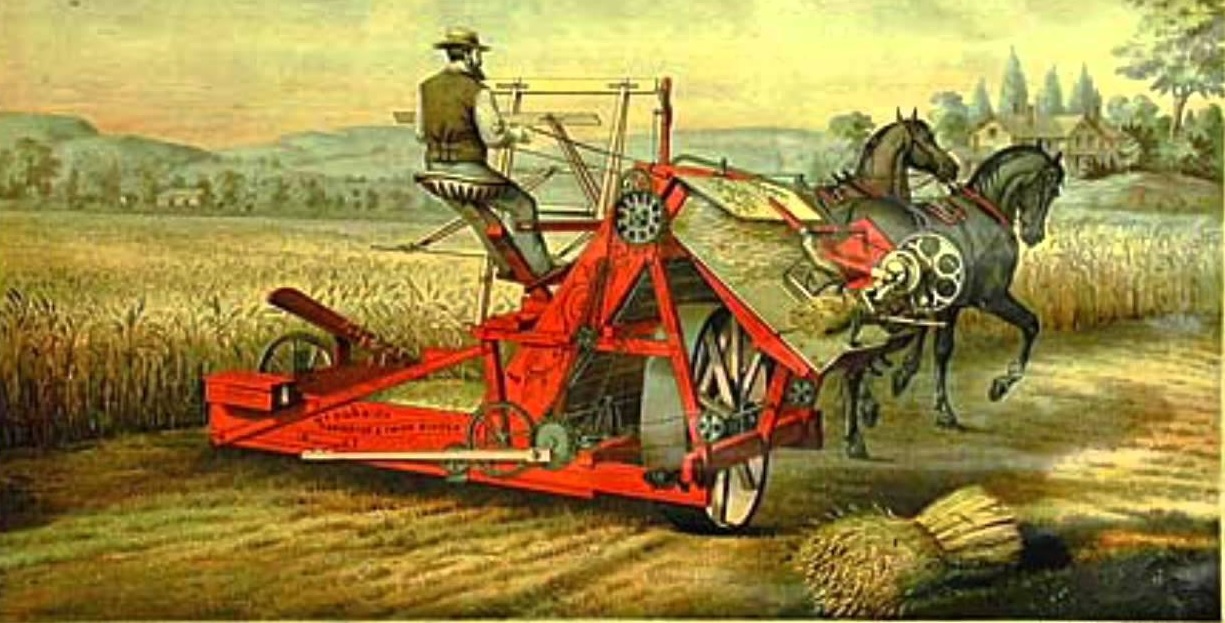

Mechanisation - new machines

Harvesting the wheat:

For cutting the corn, the sickle was replaced by the scythe, the scythe was replaced by a scythe with a cradle, that was replaced by the reaping machine which was replaced by the self-binding reaper and finally the combine harvester.

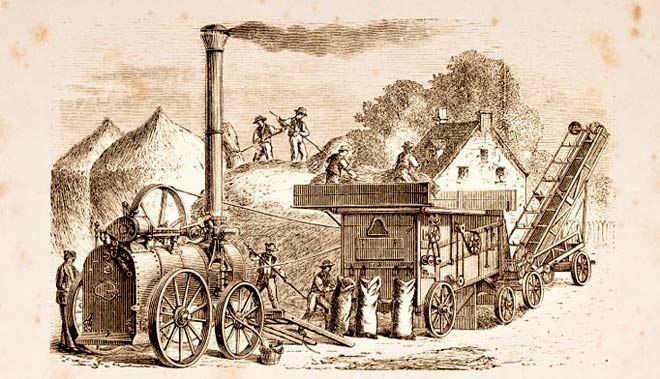

Threshing is separating the wheat seeds from the stalks.

↓ In the barn the hand flail was replaced by the threshing machine.

By 1860 every Nottinghamshire farmer had their own threshing machine. ↓

First human hands, then horses, then steam power

Click the cross on the picture to enlarge it.

The first steam engines were built in the 1700s and used for pumping water out of mines.

It was another century before they began to be used on farms.

Steam engines were used first for threshing wheat and then by 1850 for ploughing.

To plough a field by steam, two engines were placed at each side of the field and a plough attached by iron ropes was pulled across. The engine then moved forward and the plough was pulled back.

In a day, steam engines could plough ten times the area that horses could, but there were problems.

They were big and heavy and expensive. They had to be constantly supplied with water and coal which had to be brought along country lanes to the farm. Boilers sometimes exploded because they were not strong enough to withstand the pressure of the steam. The engines very heavy and compacted the soil or they sank in soft soil. They would sometimes would collapse bridges designed for horses and carts.

And so horses remained the mains source of power on the farm into the twentieth century.

Moving farm produce by rail

As coal mining grew in Nottinghamshire, and the textile industry grew in the city of Nottingham, the population grew. More and more people wanted more and more food and farmers got good prices for corn, vegetables, fruit and livestock.

And when a railway station opened at Barnstone in 1879, it was easier for farmers to get their goods to market. For the first time, local dairy farmers were able to sell liquid milk in Nottingham. So the farmers in the Vale of Belvoir kept more cows to produce more milk, cheese and butter.

(For more on Victorian Railways, click.)

Not just beans and turnips . . .

By the end of the 19th century the range of crops grown in Nottinghamshire had expanded enormously from wheat, beans and turnips.

Crops now included brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflowers, carrots, celery, onions and rhubarb. Apple, plum and damson orchards were planted. Liquorice was grown at Worksop and dyer’s weed at Scrooby for making yellow dye. Hops for flavouring beer were grown at Retford, Southwell and Tuxford.

Cropwell Bishop was famous for sheep, Ruddington for cattle, Carlton-on-Trent for shire horses, Edwinstowe for hunter horses and Colston Basset for pigs.

It was the railways that made the difference.

Farms and farmers in 1881

James Stokes - Barnston Lodge 302 acres

Isaac Barratt - Langar Lodge 290 acres

Eliza & John Blore - Crankwell Lodge 296 acres

William Stokes - Smite Hill 180 acres

George Goodwin - The Limes 420 acres

Edward Griffin James - Newlands 315 acres

George Kemp - Langar Grange 333 acres

William James - Langar Hall 340 acres

John Barratt Farm Bailiff - farm not named 207 acres

Elizabeth Stokes - Bottom House Farm 55 acres

Anne James - farm not named 150 acres

Mary Pacey - Northfield House 359 acres

Joseph Stokes - Road Farm, Barnston

Henry Lamin Miller - Colston Road, Harby

William Braithwaite Stathern – farm not named 277 acres

A Golden Age of Farming - for children?

From the Stone Age to the Victorian era, children were expected to work to earn money for the family. In 1870 school was made compulsory for children for children between the ages of 5 and 12. But in country areas, there was still farm work to be done.

In the headteacher's logbooks for 1863 to 1879 of Bingham Wesleyan School, schoolmaster, Thomas Jones, recorded reasons for children being absent:

February - bean dropping (planting)

April - bean and potato dropping

May - weeding

June - picking gooseberries

June and July - hay making

August - harvest, fruit gathering, bird scaring

September - potato gathering, gleaning

November - pulling carrots

Besides these jobs, children were needed for stone picking, tending the horses and helping with ploughing. Girls were often taken out of school to look after younger brothers and sisters while their parents worked in the fields.

Even when children did come to school, they would sometimes go home for dinner and not come back. They were working with their their fathers in the fields or in the orchards.

How we lived

↑ Langar village in 1899

The black rectangles represent buildings. In 1899 most houses were on Main Street - look for the Smithy and the Inn, The Unicorn's Head. (People also lived out of the village on farms.)

↑ Langar village in 2018

The brown rectangles represent buildings. There are still houses on Main Street, but many new houses have been built in the fields east of Main Street.

New houses

During the farming depression at the end of the wars with France, farmers and landlords could not afford to repair the workers' houses and many houses were in poor repair.

By the middle of the 19th century, with the Golden Age of English Farming, landlords began to improve their workers’ houses. The old timber-framed buildings were pulled down and new houses were built of brick.

When John Wright bought Langar Hall in 1818 and the manor of Langar and Barnstone, he owned most of the land in this area (and a lot of land in other places too). He knocked down the old cottages and had them rebuilt in brick.

Victorian houses on Main Street, Langar

Weblinks

and Horse Power

- videos on Youtube from DiscovARCountryside.

These links take you out of this website.

From horse power to steam power

Click to watch a modern video showing how steam ploughing was done in the early 20th century.