The Middle Ages - and beyond . . .

St Andrew's church, the Cathedral of the Vale

Go back to The Middle Ages. See also Rectors of Langar, Langar Rectory,

Barnstone church and The lost church of St Ethelburga.

Langar church in Norman times

Nobody knows if there was a church at Langar in Anglo-Saxon times.

But we do know there was a church here in Norman times. The Domesday Book, which was written for William the Conqueror in 1086, mentions a church here, which was probably built jointly by lords of the manor William Peverel and Walter of Aincourt.

↑ The photograph shows a simple Norman church at Elston near Newark, just 13 miles north of Langar. The first church at Langar might have looked like this,

but

nobody knows whether the church mentioned in the Domesday Book is Langar church or is it the lost church of St Ethelburga ???

Langar church in the Middle Ages - the 13th century

If there was an earlier church building, there's nothing left to see of it now.

The oldest parts of Langar church that you can see date from the 13th century - it might have been Sir Robert de Tibetot who rebuilt the church when he became the lord of the manor in 1285.

Although some parts of the building have been altered over the years, the church may look much as it did over 700 years ago.

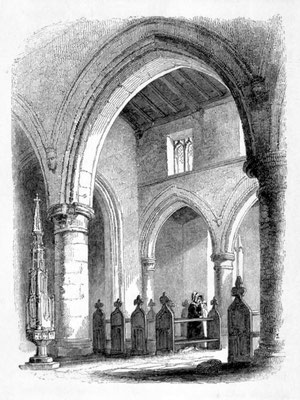

↓ The pictures below show parts of the church which are in 13th century style:

the tower, the pillars and arches inside the church, many of the windows and the arch of the entrance door are in Early English style and may be 700 years old.

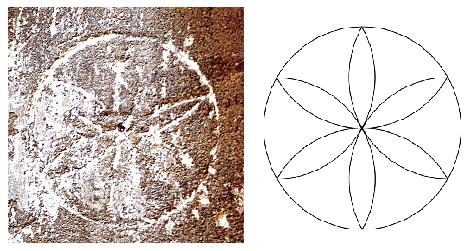

Medieval graffiti

You need to look carefully to find it, but many medieval churches have graffiti scratched on the stonework. They are often called 'witches' marks'.

In the Middle Ages people scratched pictures or patterns on the wall of their church, inside and out, to bring good luck or to protect against evil.

You can find many letters, patterns and pictures: the letters VV (Virgin of Virgins) or AM (Ave Maria = Hail Mary) referring to Jesus's mother, the Virgin Mary. Many are patterns like flowers with 6 points or pentangles with five points designed to trap evil spirits. And there are pictures of ships, churches, musical notes and windmills.

The most common is the hexafoil. There is a hexafoil on the pillar at the back of the south aisle at Langar amongst many other marks. However, the patterns are very lightly scratched and they are not easy to see. This may be so that the evil spirits could not see the patterns until they were trapped inside. But nobody knows.

Langar church in the Middle Ages - the 15th century

The main door was made of English oak in the 15th century and has a small wicket door in the centre; this would let in less cold and draughts than opening the main door when people came to church. The porch was probably built about the same time.

The hinges on the inside of the door were replaced in Victorian times. Look carefully on the door handle to see the name of William Gretton, the village blacksmith in the 19th century. He lived at Chestnut Farm on Main Street opposite the Unicorn's Head public house.

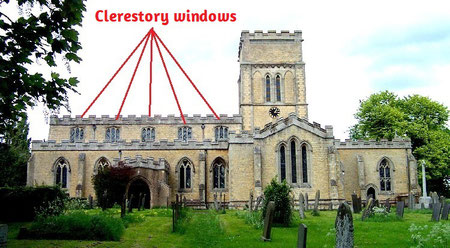

Also in the 15th century, the roof of the nave was made higher and five clerestory windows were made to let in more light. Battlements were built along the tops of the walls which make the church look rather like a castle, probably to match Langar Hall.

The tower was also made taller. This may have been the work of the lord of the manor, Sir John Scrope (1437-1498). He fought many battles for the king and did not spend much time at Langar.

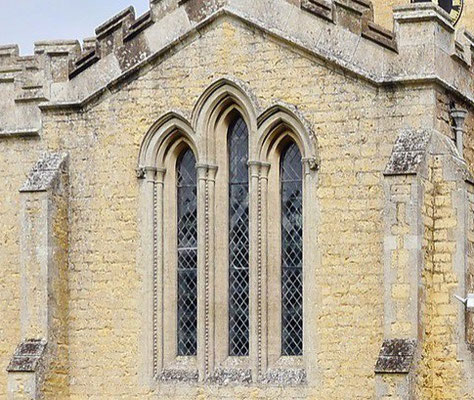

← During the 15th century architects and builders began to make larger and more complicated windows. The large east window at Langar is in Perpendicular style.

Langar church in Tudor times

The 16th century

Langar church is famous for its tombs.

The Chaworth family lived at Wiverton Hall. Their tombs are in the north transept:

- The oldest tomb commemorates George Chaworth of Wiverton Hall who died in 1521 and his wife Katherine who died in 1517.

- A marble tomb with two recumbent (lying down) effigies (statues) of John Chaworth, wearing Tudor armour, who died in 1558, and his wife Mary with their 15 children mourning around the base.

- A white alabaster recumbent effigy of Sir George Chaworth, also wearing armour, who died in 1587. Effigies were brightly painted in the Middle Ages. Although the paint faded long ago, traces of colour can still be seen.

The photographs of the Chaworth tombs at Langar church below are from the Southwell & Nottingham Church History Project website.

See also Langar church in Tudor times and Tudor rectors.

Langar church in the time of the Stuarts

The 17th century

The wooden rail in front of the altar dates from Stuart times - it is Jacobean, meaning that it dates from the time of King James I (reigned 1603-1625) (Jacobus is Latin for James.)

The octagonal wooden pulpit is also Jacobean. It is unusual in having pictures painted on it.

Click to enlarge the pictures.

Langar church is famous for its tombs.

The Scrope family lived at Langar Hall. Their tomb is in the south transept:

- A magnificent tomb with columns and a canopy with two recumbent (lying down) effigies (statues) of Thomas, Lord Scrope who died in 1609 and his wife Philadelphia. He is wearing armour and the cap of the Order of the Garter; Lady Scrope who died in 1627 is shown in a full flowing mantle and ruff with her hair in the latest fashion.

- A statue of their son Emmanuel kneels at their feet.

The photographs of the Scrope tomb at Langar church below are from the Southwell & Nottingham Church History Project website.

The Scropes and the Chaworths were buried in magnificent tombs inside the church.

Where was everyone else buried in Tudor times?

You had to be very very rich to have a tomb made like the Chaworths and the Scropes. Only very important people were buried inside a church. And the cost of a tomb was thousands and thousands of pounds. Everyone else was buried in the churchyard without a stone to mark their grave. Hundreds of ordinary people from Langar and Barnstone have been buried in St Andrew's churchyard for hundreds of years but nobody knows who they were or where they are.

The Langar Protestation Return 1642

During the reign of King Charles I, Parliament was worried that the Protestant England was in danger from Roman Catholics. A law was passed to make all men over the age of 18 swear to live and die for the Protestant religion.

In 1642 all men had to sign a document known as the Protestation Return. In the parish of Langar cum Barnstone, all the men, 85 of them signed and none refused. (Interesting that all of them could write! There must have been a good village school.)

I do, in the presence of Almighty God, promise, vow, and protest to maintain, and defend as far as lawfully I may, with my Life, Power and Estate, the true Reformed Protestant religion, expressed in the Doctrine of the Church of England.

All change . . .

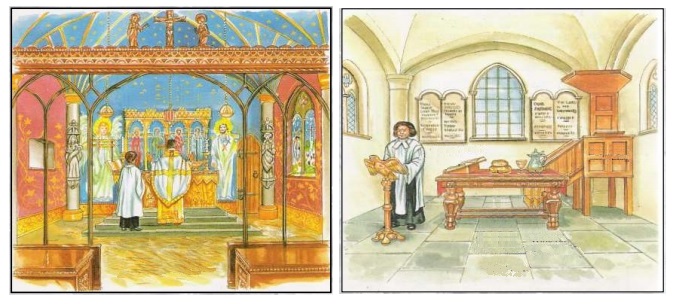

Churches have changed over the years as styles, fashions and beliefs have changed.

And so has St Andrew's.

In the Middle Ages there were no seats - the congregation stood for the church service. And the priest held the service of the Mass (Holy Communion) at the altar behind a wooden screen where the people could not see. The service was in Latin which the village people could not understand. The walls were brightly painted with pictures of the saints and stories from the Bible.

When Henry VIII (r.1509 -1547) separated the Church of England from the Roman Catholic church in 1534, not much else changed, except the king was Head of the Church of England not the Pope and the Bible was read in English not Latin.

Edward VI (r.1547-1553),

the first protestant king of England, radically changed the Church of England. Services were now all in English using a new prayer book written by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer (who was born at Alsockton just 6 miles north of Langar).

Priests could no longer wore brightly coloured vestments and were now allowed to marry. Churches had to be plain - King Edward sent his soldiers to smash stained glass windows and statues and to paint over the wall paintings.

In Edward VI's reign a list (inventory) was made of the things in the church:

(In Tudor times, Roman numerals were handwritten as: i = 1 ij = 2 iij = 3 iiij = 4 v = 5)

Lang'r

first one chalis of Silver wt a cover for the same & also one crosse of brasse Also ij bras candilstiks that standith over the alt' Also iiij alt’ clothes of lynyn clothe Also iiij towills of lynyn clothe Also one for fronte to the alt' of paynted lynyn cloth

Also fowre vestmentes whereof one of blacke worstyt Also one othr of gren Sattyne of burgesse one other of them wroght grene cruells & silkes the forthe of the' of lynyne wroght wt silke & goold wt othr nesesaris belogy’gs to the’ Also a coope of the same lynen wroght silke & goold

Also two cruytes Also iiijor Belles A peyre of Sensors of bras Also j Surplis wt Slevis.

Robert Clarke parson

Nobody knows what happened to the things on this list. They are just the sort of Roman Catholic items that Edward VI hated.

Langar

- First one chalice of silver with a cover - for the Communion wine.

- And also one brass cross - the cross that is carried to the front of the church when the priest arrives.

- 2 brass candlesticks standing on the altar.

- Also 4 linen altar cloths (like table-cloths), 4 linen towels (for drying the communion plate and chalice), one painted linen altar front.

- 4 vestments (the special clothes that priests wear for church services) - one of black worsted (high quality woolen cloth - black for funerals), another of green satin, another green one embroidered with silk (green for ordinary Sundays) and a fourth embroidered with silk and gold (for Christmas and Easter) with everything else necessary - rope belt, scarf etc.

- Also a silk cope - (like a cloak) embroidered with gold.

- 2 cruets - jugs for holding communion wine or water.

- 4 bells - handbells rung when the bread and wine are blessed.

- A pair of brass censers - containers for burning incense.

- 1 surplice with sleeves - a long white item of clothing worn by priests.

Queen Mary (r.1553 - 1558) was a Roman Catholic and changed the Church of England back to the old religion. Many churches had hidden their paintings and statues and screens before King Edward's soldiers came and these were brought out again.

←

Click the picture of Our Lady of Egmanton, Nottinghamshire restored in Victorian times to look like a medieval Catholic church.

From 1534 when Henry VIII separated the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church, it must have been a very confusing and upsetting time for people who took their religion very seriously. But if you protested you would end up in prison - or worse.

Above left: celebrating Mass (Holy Communion) up until the time of Henry VIII.

Above right: A service of Holy Communion in the time of Edward VI.

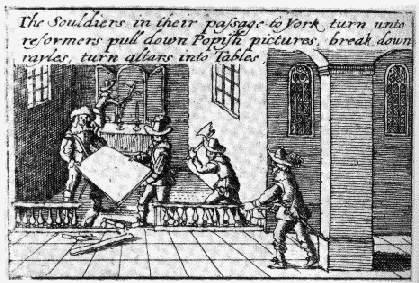

All change . . . and back again

Below left: ↓ King Edward's men clear the church.

Below right: ↓ Queen Mary's men put it all back again.

Queen Elizabeth I (r.1558 - 1603)

was a Protestant who wanted to be tolerant towards Roman Catholics. She had no sympathy with Protestant extremists who wanted to get rid of music, vestments, paintings, statues, incense and bells.

In her time church buildings changed little, though as sermons became longer, wealthy people sat on benches or pews.

The Stuart kings - Charles I, Charles II, James II - all had problems being the head of the Protestant Church of England but also secretly being Roman Catholic.

And in the middle of the Stuart period, after the execution of Charles I, came the Commonwealth and Oliver Cromwell with their Puritan ideals.

It was as it had been in Edward VI's time: churches had to be plain - stained glass windows and statues were smashed and pictures were removed or painted over.

With the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 under Charles II, the Church of England went back to how it had been earlier. However, by now, very little medieval furniture, paintings, vestments and books still survived.

Langar church in Georgian times

The 18th century

In the 18th century a gallery was built at the back of the church (west end) for the lord of the manor and his family, with a covered walkway from the back of Langar Hall. This was to cater for the privacy and comfort of the Howe family.

So how did they get up to the gallery? Was a stair built outside the back of the church and a doorway through the window? This certainly happened at other churches. Was it like this at Langar church? Nobody knows - but probably!

Nobody knows if box pews were made at Langar during the 18th century. Instead of benches these had a tall wooden wall round them with a door. In many churches, members of the congregation had to pay rent to use a pew. They too were made for the privacy and comfort of people who could afford it. Were there box pews at Langar? Nobody knows - but probably!

↑ The picture above shows Tithby church which still has its gallery and box pews.

In 1750 a new roof was installed. It's still there. On one of the beams the workers wrote their names - Carpenters Richard Wright, Henry Wright September 29th 1750.

But by the end of the 18th century a visitor wrote that the church was 'a fair structure'

but 'a little out of repair'.

Victorian Langar - The 19th century

. . . back to the Middle Ages

The church of St Andrew, Langar changed many times over the centuries. By the 19th century many religious people believed that many of these changes were bad. They thought that the ways of worshipping and the architecture of churches had been at their best in the Middle Ages. The favourite styles of the Victorians were the Gothic styles of the 14th century, known as Early English style (1190-1250) and Decorated style (1250-1350).

Nowadays people like to keep evidence of the changes that happened in the past, but the Victorians wanted their churches to look like medieval churches. So they removed anything that had happened in between.

They took out the Georgian box pews and galleries and altered the windows to Early English or Decorated styles. And this is what happened at Langar church.

Sometimes the Victorians would completely demolish an old medieval church and rebuild again it in medieval style.

Spot the difference!

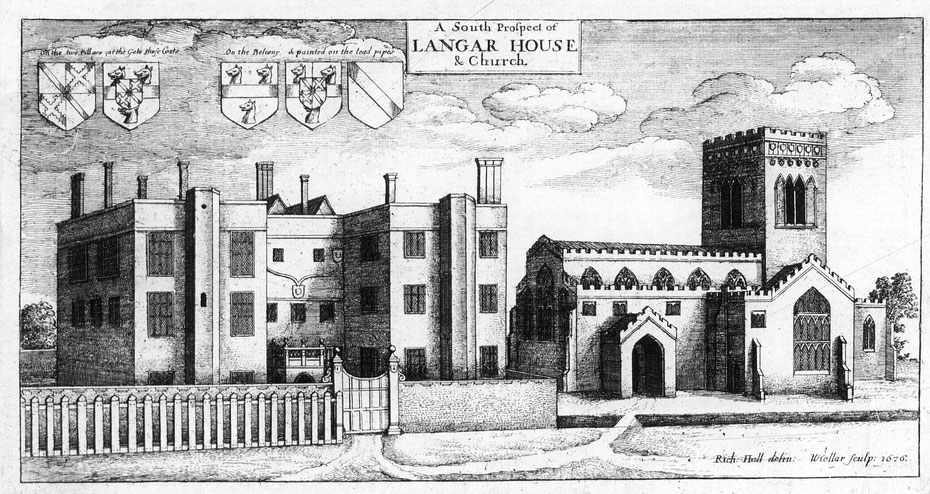

The picture on the left shows Langar church in 1767.

The picture on the right is how the church looks after the Victorians restored it in the 1860s. (Look at the windows.)

The Rector of St Andrew's at this time was the Reverend Thomas Butler. In the 1860s, he set about restoring the church how he thought it looked in the 14th century.

A priest called Edward Trollope visited the church in 1864.

He said that Butler was then rebuilding the tower, which had been sinking, and that Reverend Butler had nearly finished rebuilding the rest of the church in the Decorated Gothic style.

Rebuilding a church is not cheap! Where did the money come from?

People donated money - £55 from John Chaworth Musters of Wiverton Hall whose ancestors are buried in the church, £31 from Earl Howe whose ancestors had been lords of the manor, and 5 guineas (£5.5 shillings) from Rev Joshua Brooke, rector of nearby Colston Bassett. But by far the greatest amount was given by the rector of Langar himself, Rev Butler. In 1865 he gave £475.14.0 and promised another £100.

In today's money this is over a million pounds!

Here is a problem: The Victorian architects and stone masons were so skillful at copying medieval windows that it's often impossible to tell which are genuine medieval windows and which are Victorian copies of medieval windows. ↓

↑ Are the windows medieval and 700 years old - or are they Victorian and 150 years old?

Nobody knows!

And another thing!

The genuine 13th-century columns (left) are a different colour from the stone on the outside of the church (right).

Why? Because Thomas Butler had the whole of the outside of the church covered in Ancaster Stone, brought from a quarry in nearby Lincolnshire. It is a harder stone than the local Langar stone used to build the medieval church and lasts longer. And it's posher! (Ancaster stone was used to build Nottinghamshire's poshest house - Woollaton Hall.)

So is Langar church medieval?

Yes but No! NO but YES!

The 20th century

In 1907 Langar was described as 'one of the deserted villages of Nottinghamshire'.

And the church was in poor state. The roof of the nave was restored in 1904 at a cost of £350 to stop the rain coming in, The south transept and aisle were restored in 1905 for £105. Even so the church was in poor state.

It was not until 1997 (over 90 years later) that the roof of the north transept was mended; and the chancel roof was mended one year later.

In the year 2000 the Millennium Room was built as a meeting room and kitchen.

Stained glass windows

In 2017 the Parish of Langar cum Barnstone was made part of a wider group of parishes, called the Parish of Wiverton in the Vale which includes the churches of St John the Divine, Colston Bassett • St Giles, Cropwell Bishop • St Michael and All Angels, Elton • All Saints, Granby cum Sutton • St Andrew, Langar cum Barnstone • Holy Trinity, Tythby cum Cropwell Butler.

Take a seat - if there is one!

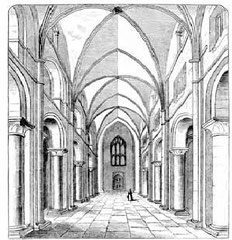

Medieval ↑ Above (Click to enlarge.)

Left: A medieval church with no seats - standing room only - Blyth monastery, Nottinghamshire

Centre: Simple benches were provided for wealthier church goers.

Right: Benches got fancier!

18th century ↑ Above (Click to enlarge.)

Left: As sermons got longer, the whole of the church was filled with pews fixed to the floor

Centre: By the 18th century most churches had box pews like these at Tithby.

Right: The lord of the manor had his own special pew - Teversal church, Nottinghamshire.

20th century ↑ Above (Click to enlarge.)

Left: The Victorians took the box pews out and replaced them with lower benches like medieval pews. These are the Victorian pews at Langar church in 1903.

Centre: The Victorian pews were taken out of Langar church and replaced with chairs in 1971.

Right: Nowadays the chairs can be arranged in any way to suit the type of service.

The bells of Langar

Langar church had four large bells up in the tower dated 1601, 1611 and 1636 cast by Henry Oldfield of Nottingham and his son. The bells were melted down and recast and a fifth bell was added by Taylor's of Loughborough in 1859.

This heavy ring of bells was rung from the floor of the church until 1969 when another floor was built higher up the tower.

Click to hear to a bit of bellringing at Langar

on a very shaky YouTube video

or - better - Watch a band bellringing

at East Markham, Nottinghamshire, on YouTube.

These weblinks take you out of this website.

Plan of Langar church

St Andrew's church, Langar - PHOTO GALLERY

And finally - we've come to a dead end:

the Graveyard

Langar churchyard is in two parts. The small area north of the church has memorials to some well-known people in the history of Langar:

- John Chaworth Musters - A slate tablet on the church wall reads:

Beneath this spot near the dust of his ancestors lies John Chaworth Musters Esquire. He was born at Wiverton, Jan, 9th. 1838, and in his 12th year inherited from his grandfather John Musters Esqre the estates of Colwick, West Bridgford, Edwalton, Annesley, Felley, Tithby & Wiverton. He married in 1859, the eldest daughter of Henry Sherbrooke Esqre of Oxton by whom he left 3 sons and 2 daughters. He died from the effects of scarlet fever at Aumont in France on the 17th. of November 1887 in his 50th year.

(Other memorials to the Chaworth family are inside the church in the north transept).

- Penn Curzon Sherbrooke - Captain of the South Notts Hussars Yeomanry and for 17 years Master of the Sinnington Hounds.

- William Butler – son of Reverend Thomas Butler - he died at 6 months old.

- Thomas and Annie Bayley - Thomas Bayley, a wealthy coal owner and Liberal MP for Chesterfield. His wife was the daughter of composer Henry Farmer. She bought Langar Hall in 1860. The stained glass window in the church is in their memory.

- Percy Lambe Huskinson - He married Muriel, daughter of Annie Bayley who carried on living at Langar Hall.

- Geoffrey Neville Bayley Huskinson – He inherited Langar Hall on the death of Muriel Bayley in 1933. Geoffrey was president of the Notts County Cricket Club and played rugby for England.

- Reverend Edward Gregory - In 1793 he discovered the comet Gregory-Méchain.

- Imogen Skirving who set up the hotel and restaurant at Langar Hall, killed by a car in 2016 in Menorca.

The main graveyard is south of the church:

William Gretton – the village blacksmith whose name can be seen on the ironwork of the church door.

Major General Sir Miles Graham KBE CB MC - He was awarded the Military Cross serving with the Life Guards in the First World War. With the outbreak of the Second World War, he formed the 1st Cavalry Division and was posted to Palestine.

He was appointed Chief Administrative Officer to Field Marshall Montgomery and served in Egypt, Cyrenaica, Tripolitania, Sicily, Italy and the Normandy landings. Sir Miles and Lady Graham lived at Wiverton Hall at the end of the war.

-

William Simon - The oldest gravestone still visible is that of William Simon:

HERE lies ye Body of William Simon senior, son of William Simon by Barbra his wife. He died ye 8th Day of May 1713. aged 50 y.

Reader stand still and lend a tear Upon the dust that sleepeth here

And whilst thou readst ye slate of me Think on the glass yt runs for thee.

The Belvoir Angels

The Belvoir Angels are a type of gravestone found only in the Vale of Belvoir. In St Andrew’s churchyard there are nine Belvoir Angels.

These gravestones are carved from hard-wearing Swithland slate from a quarry in nearby Leicestershire. At the top of the gravestone is carved an angel's head flanked by wings, which represents the person's soul rising to heaven. There is often the symbol of an hour glass (to show how time runs out) and crossed bones.

The Belvoir Angels date from 1690 to 1759 and are very well carved, though the letters and spelling and grammar are often poor.

But who made them? Nobody knows!

And also lying in the churchyard in unmarked graves are the bones of hundreds of ordinary people from Langar and Barnstone who were buried here for hundreds of years, though nobody now knows their names or where they lie.

May they rest in peace. ✠