The Middle Ages

1154 - 1485

START: In 1154 Henry II became king ending the civil war at the end of the Norman period.

END: The Middle Ages ended with the death in battle of Richard III in 1485.

Note: The Middle Ages was given its name by historians of the 17th century who saw it as an uncivilised period between the Roman Empire and their own time.

Kings of England of the Middle Ages with the dates they reigned:

Henry II 1154 - 1189 Richard I 1189 - 1199 John 1199 - 1216

Henry III 1216 - 1272 Edward I 1272 - 1307 Edward II 1307 - 1327

Edward III – 1327 - 1377 Richard II 1377 - 1399

Henry IV – 1399 - 1413 Henry V 1413 - 1422 Henry VI 1422 - 1461

Edward IV 1461 - 1470 Henry VI 1470 - 1471 Edward IV 1471 - 1483

Edward V 1483 - 1483 Richard III 1483 - 1485

See also Lords of the Manor in the Middle Ages, Langar Hall, the Manor House, Langar church, St Andrew's,

Rectors of Langar, Barnstone church, St Mary's and The lost church of St Ethelburga.

For most people in the Middle Ages life was all about

FARMING

Langar and Barnstone have always been about farming. If you didn't grow your own crops or keep your own animals, you starved!

Farming in the Vale of Belvoir

When the Normans arrived in England, this part of Nottinghamshire was the most productive farmland in the county - most of it was arable land for growing crops rather than pasture for keeping animals. But the pattern of farming was changing.

By the Middle Ages, instead of small farms scattered across the Vale of Belvoir, people were coming together to live in small villages. Around the village were large open fields shared by the villagers.

Open fields in Langar

The open fields in Langar and Barnstone were shared by people in both villages.

The fields were called Town Field, Middle Field and North Field.

Nobody knows exactly where the fields were, but Town Field was probably in between Langar and Barnstone, Northfield was north of Langar on Bingham Road where Northfields Farm is now and Middle Field was somewhere in the middle!

The open fields are gone now. They were enclosed in 1681 by the lord of the manor, Viscount Howe. But you can still see the ridges and furrows left by the system of ploughing in a number of places near Barnstone and Langar.

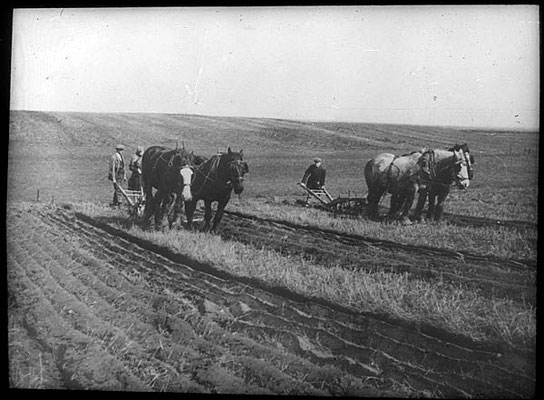

A farmer in Ireland ploughs in a traditional way to test the saying: One man, one horse, one acre a day. (An acre is about the area of a football pitch).

The square icon bottom right is for full screen.

The video links to YouTube out of this website.

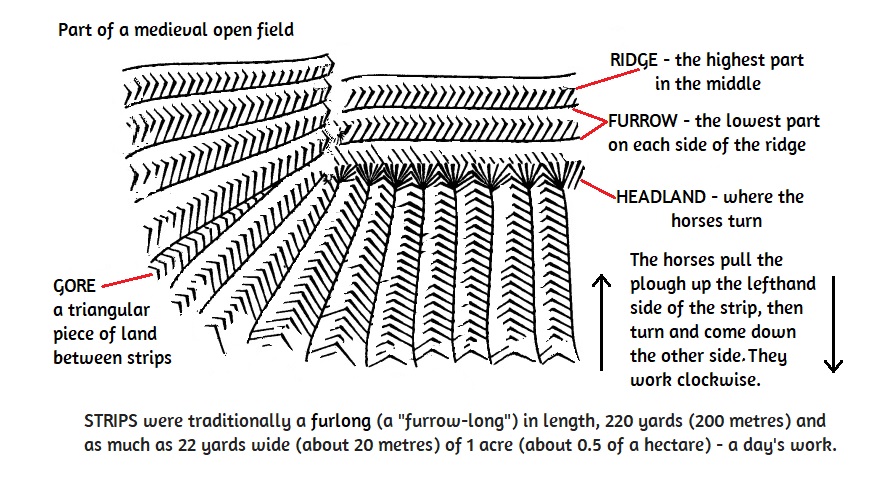

Open fields - Ridge and Furrow

The most obvious signs of medieval open fields are the ridges and furrows they have left behind.

Around a typical village there were three (or more) large open fields: they are called 'open' because they had no fences or hedges round them.

These large fields were divided into long strips. Each tenant of the manor had several strips of land in different parts of the three fields. Having strips in different fields meant that each tenant had a fair share of the good and the bad land in the manor.

The strips were long and thin because this was the easiest shape for ploughing. The length of a strip was called a furlong (furrow long).1 furlong = 220 yards (about 200 metres) which was the distance the horses or oxen could pull a plough before needing to rest.

The area of these largest strips was 1 acre (about 0.5 of a hectare). However, many strips were narrower, the smallest were 5 metres, especially on more difficult soils.

One man, on horse, one acre a day.

Ridges and furrows were caused by the way the medieval ploughs went up and down the long thin strips always pushing the soil towards the centre of the strip. Over hundreds of years, the middle of the ridge could be over half a metre higher than the furrow. This was accidental, but it meant that tenants could easily identify their own strips and it also helped to drain the land.

The map shows fields near here where you can still see ridge and furrow.

Click the pictures below for a closer look.

A remarkable image!

This image of Langar was made using LIDAR.

Q. Why is this a remarkable image?

A. Because it shows something that you cannot actually see.

LIDAR is a method used to survey the land from a plane using lasers. The laser beams see through trees and plants to the ground beneath and highlight small lumps and bumps, dips and hollows that you cannot see in any other way.

What's where? Langar village is at the top right of the image; Cropwell Road runs left-to-right below the village; from bottom-to-top up the middle of the map is Stroom Dyke.

LIDAR is very useful in archaeology because it shows up features that you cannot see from the ground. Fields that seem to be flat may have evidence of streams that are no longer there, or where buildings used to be. LIDAR can show where ancient fields were or reveal evidence of the strips in the medieval open fields. LIDAR can show evidence of the past.

↓ The map below compares the LIDAR map with an aerial view of the same area.

The smooth flat fields in the aerial view on the right are not really smooth and flat at all.

Left: LIDAR image Right: aerial view

The map above shows evidence of older fields. ↑ The small square fields are the oldest.

They date from the Iron Age or Roman times. You can see lots of ridge and furrow where the medieval strips were in the open fields. And you can see faint traces of

strips that have been ploughed out in the 20th century. Standing on the ground in one of these fields, you can see none of these features. LIDAR has shown this evidence of Langar for the first

time.

It's a remarkable image!

So why is there so little evidence of ridge and furrow now?!

Open fields with their ridges and furrows covered the landscape for hundreds of years. So why are there so few left now?

From the 18th century (and even earlier) some farmers joined their strips in the open fields together into closed fields with hedges and fences round them.

More efficient ploughs began to wear away the ridges and fill in the furrows. In the 20th century farmers levelled the ground with large tractors to make it easier for machines such as combine harvesters to gather the crops.

Ridges and furrows left by medieval farmers could still be seen in many fields until the last years of the 20th century. But in the East Midlands 94% of ridge and furrow has now been destroyed.

This is funny!

← This photograph shows a remarkable set of ridges and furrows on the golf course at Stanton on the Wolds 10 miles from Langar.

Must be tricky playing golf here!

How did the open field system work?

A typical village had three fields - some had more.

Everybody had to plant the same crops.

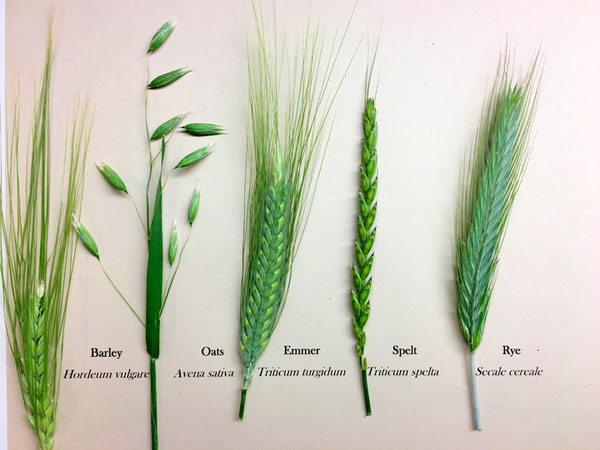

- Barley, oats, peas or beans were planted in one field in spring.

- Wheat or rye were planted in the second field in autumn.

-

And the third field would be left fallow with nothing growing. That field was used by all the villagers to pasture their animals. Livestock would also be let

onto the other fields after harvest.

Animal poo makes very good fertiliser!

The following year, a different field was left fallow with nothing growing and the crops in the other fields were changed round. It is a system known as crop rotation.

Wheat and barley were the most important crops in England.

Wheat brought the best price. Only rich people could afford to eat bread made of wheat flour.

Barley was mixed with other grains to make bread for poorer people; it was also used to make beer which was drunk in large amounts by everybody.

Farmers grew twice as much barley as wheat with smaller amounts of oats, peas, beans, rye and flax.

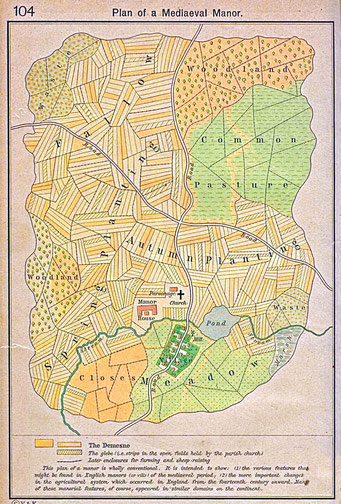

A typical medieval manor

The map shows an imaginary typical medieval village surrounded by three open fields divided into strips.

People had a number of strips of land in each of the fields for which they had to pay rent to the lord of the manor. The lord also owned his own strips in the fields and the tenants had to work on his land for nothing. In addition the priest of the village church owned land. Villagers also had to pay one tenth of what they produced to the church.

Villagers had to pay the lord for grinding their corn - he was the only one allowed to own a water mill. And he was the only one allowed to fish in the millpond.

On the map: (Click it twice to enlarge it.

- the yellow strips show the land of the lord of the manor (the demesne);

- the hatched strips with little lines across show land belonging to the priest of the parish church (glebe land);

- the rest of the strips were shared among the villagers to rent.

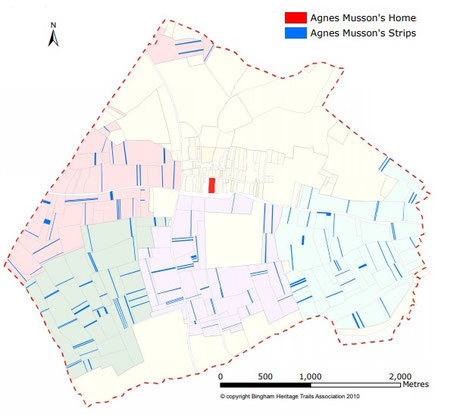

Bingham fields

This map shows how one farmer's strips were scattered across the open fields in Bingham in 1586.

Agnes Musson lived in a house in the village (red rectangle).

She farmed a hundred strips (blue) scattered across the four fields at Bingham - North, South, East and West fields. She was one of the richer farmers in Bingham.

Click to enlarge.

Villages - Langar and Barnstone

Before the Middle Ages, houses and farms were scattered across a wide area. But in medieval times in the Vale of Belvoir, villagers' houses were closely grouped together as at Langar; some villages were spread along the road as at Barnstone.

These maps are from 1899 (Victorian) and are not medieval. However, the villages may have changed little from the Middle Ages.

Houses

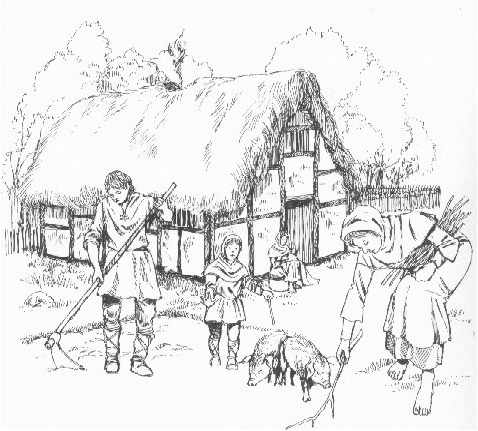

Villagers' cottages very simple - they had one room, one storey and were made of wood and mud and straw. Outside there was a garden (a croft) for growing vegetables and an pen for keeping animals such as hens or a pig.

(No houses in Langar and Barnstone survive from the Middle Ages. The oldest houses here date from the 17th and 18th centuries.)

Not everyone in the village could afford to rent strips in the fields. About half the families in a manor had no land at all and had to work for larger landholders.

Waste, woodland and closes

As well as arable land for growing crops, there was common pasture land known as waste, where villagers could graze their livestock (usually pigs and sheep, perhaps a cow).

There may also have been woodland for firewood and timber and for grazing the pigs. However, woodland was scarce in the Vale of Belvoir - the trees had been felled to make way for fields many years ago.

Some people could afford to fence or hedge land (closes) for their own use as allotments for vegetables, orchards for fruit or paddocks for horses.

Some tenants who rented land also had livestock, including sheep, pigs, cattle, horses, oxen, and hens. Most people could rarely afford to eat meat, but if they did it was pork. Sheep were kept for wool not meat.

Only a few rich landholders had enough oxen to make up their own plough team of six or eight; most villagers shared a plough team with their neighbours.

Matillda de Herdeby's contract 1340

- a contract that ruled the lives of most people in the Middle Ages -

Having trouble reading the medieval handwriting ??? !!!

↓ This is what it says . . .

Tenentes tofftorum in bondagio

Matillda de Herdeby tenet j tofftum in bondagio et reddit per annum . ij . solidos . vj denarios . terminis ut supra Et dabit auxilium secundum numerum animalium suorum Et debet meterium in Autumpno ad Magna precaria domini cum tota familia excepta . uxore domus Et valet operis illius diei per estimacione ij denarios et habebit j repastum et valet j denarius et sic valet opus illius diei ultra repastam j . denarius. Et dabit pro quolibet pullano masculino . iij . denarios . pro tolleneto Et valet tollenetum per annum . [...] Et dabit pannagium porcorum bis per annum ut supra et valet pannagium per annum [...] Et dabit Merchetum et LeyrWytum pro filiis suis.

Hope that's some help !!!

but probably not . . .

Let's explain:

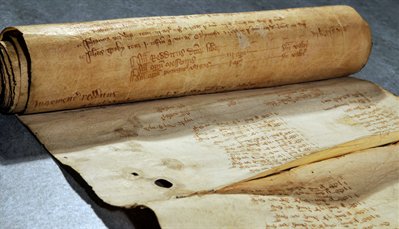

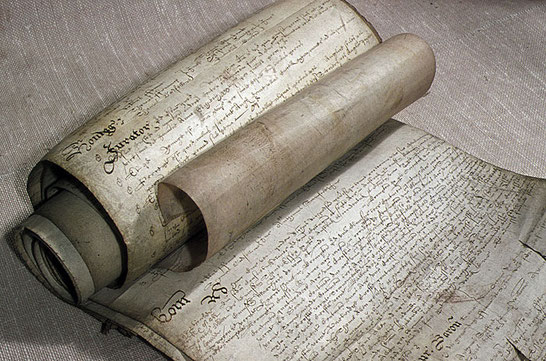

Matillda de Herdeby's contract is part of the records of the manor court of Langar and Barnstone. It is a document written on animal skin that has survived for 700 years. It is written in Latin as were most legal documents at that time.

Matilda de Herdeby was a woman who was living in Langar or Barnstone in 1340. Her name suggests that she originally came from nearby Harby.

She was a bondage tenant (a villein), which meant that she rented her house and land from the lord of the manor. She lived in a toft (a house with some some land) in the manor of Langar and Barnstone. Nobody knows exactly where.

This contract gives details of the rents and services she owed to her lord - this would be the same for the other villeins in the manor. The lord of the manor in Matillda's time was Sir John Tibetot. (Click here for Lords of the Manor.)

This is Matillda's contract

↓ translated into English . . .

Bondage tenants of tofts.

- Matillda de Herdeby has 1 toft in bondage and pays 2s 6d (2 shillings and 6 pence) a year.

- And she owes harvest work in autumn at the chief service of the lord with her whole family except the housewife. And the value of the work of that day shall be assessed at 2d. And she shall have one meal to be valued at 1d. And the afternoon’s work shall be valued at 1d.

- And she owes an aid of the above-mentioned number of her animals [blank]. And she shall give as toll for every male foal 4d.

- And she shall provide pannage for swine twice in the year valued at [blank].

- And she shall pay merchet and leywrite for her daughters.

Translated from Latin by Professor L V D Owen of the University of Nottingham in 1946 - adapted.

Notes:

[blank] means the amount has not been written in the document.

Money

s = shilling; 20 shillings = £1.

d = pence; 12 pence = 1 shilling.

Dates Rents were paid on the Quarter Days following the pattern of the Christian year:

Christmas - 25 December

Lady Day - 25 March

Midsummer (Feast of John the Baptist) - 24 June

Michaelmas - 29 September

And here's some help understanding

↓ what it means . . .

- Matillda was a bondage tenant or villein, a peasant who paid rent and did farm work for the lord in exchange for a house and the right to farm land. A toft was a house with land. Lords had a lot of power over people in their manors. Peasants had to swear loyalty to their lord and were under his control in most aspects of their lives.

- Like most people in the manor, Matillda’s family had to spend time working on the lord’s land, in this contract at harvest time. But here the housewife (Matillda herself) is not included. Perhaps this shows the importance attached to ‘women’s work’ in the home. While men worked on the land, the housewife had her own status as manager of the household, which should not be disturbed. All the more important if Matillda had no husband - he is not mentioned here.

- 'Aid' is a tax Matillda must pay to keep each animal. The type and number of animals is not given here. Foals (baby horses) were taxed separately.

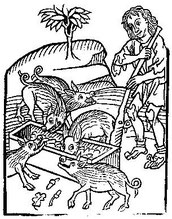

- Pannage was taking the pigs out into the forest to eat the acorns and other autumn fruits.

- Matillda had to pay 'merchet and leywrite' for her daughters. This was for the lord’s permission for a daughter to marry a man from another manor. It was compensation for the fact that their children would live elsewhere and not give the lord service.

Matillda's husband is not mentioned. It is likely that he was dead, otherwise as a man, the contract would have been with him as the head of the household.

Matillda may also have rented strips in the open fields which are not mentioned in this contract. She would have to pay rent for the strips of land in the fields. And her family had to work in the lord's fields at certain times of the year - ploughing and planting in spring, harvesting at the end of summer, for instance.

This contract was the same for most people in Langar and Barnstone, and all of England, for hundreds of years.

Court rolls

Court rolls were the written records of the manor court, disputes and decisions made about local matters. These might be about who owed money or service to the lord, arguments between neighbours or crimes.

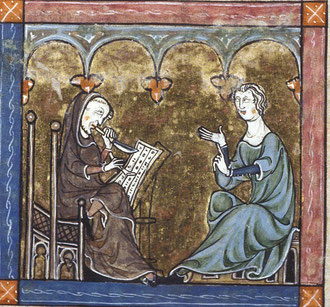

Few people could read in the Middle Ages and even fewer could write. The main people to do so were priests of the Church, who read the Bible and church services in Latin, and monks who copied out new prayer books and Bibles.

However, more and more lords wanted a written record of what went on in their manors: how much people owed them, what contracts the peasants had, how much money was spent, what decisions were made in the manor court.

Scribes The lords needed people who could write: scribes. Cathedral schools (locally at York and Southwell) taught young men (and some women) to read and write in Latin as well as to to keep accounts and write legal documents. It was the scribes who wrote the court rolls.

Parchment The records of the manor were written on parchment. This was made from the skin of sheep or goats, scraped and stretched thin.

Pens Scribes made their own own pens (quills) from the tail and wing feathers of geese or swans. They wore out quickly and were sharpened with a pen knife.

Ink They made their own ink from a mixture of iron salts, oak galls and gum, stirred for three weeks and then diluted with water.

Court rolls When a parchment was full of information from the manor courts, it was rolled up into a scroll, which is why they are called court rolls. The result was a document that would last for a thousand years!

The Medieval Farming Year

6 days a week for 52 weeks from dawn till dusk. But you did get Christmas Day off.

(That's not quite true! There's something for you to investigate.)

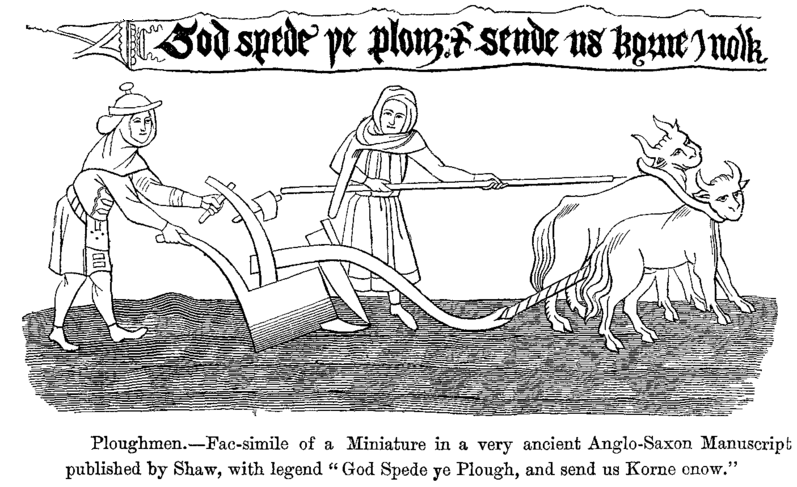

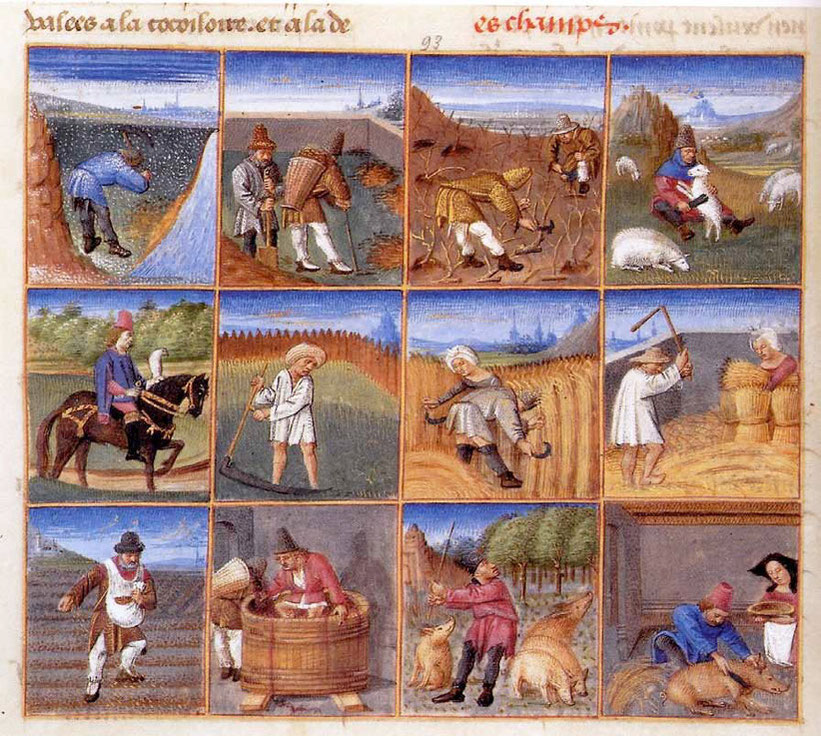

Above ↑ The farming year

(This calendar comes from a book written in France in the Middle Ages. Farming life was similar in England. Books in the Middle Ages were very expensive and for rich people only. These pictures were made to entertain wealthy people and do not show a true picture of the hardships of farming life for ordinary people.)

Here are some of the farming jobs that had to be done, year after year after year after year, each and every year, whatever the weather.

- January: Clear ditches, cut wood, spread manure.

- February: Mend fences, manure the soil.

- March: Plough the fields; sow the wheat seeds.

- April: Plant onions and leeks: piglets are born.

- May: Weed the wheat field, do home repairs, sow beans, plant garden vegetables.

- June: Start harvesting the hay.

- July: Finish harvesting the hay; start harvesting the wheat.

- August: Finish harvesting, gather the straw, plant turnips.

- September: Harvest the garden vegetables, plough the fields and sow the winter wheat, take animals to sell at market.

- October: Send the pigs into the woods to eat acorns; thresh the wheat.

- November: Collect firewood for winter.

- December: Kill the pigs, spread manure for next year's crops.

- January: Start all over again.

Do it yourself - or die

As well as the work on the land you rented and the work you had to do on the lord’s land and the tenth of your produce that you had to give to the church, there was work to do at home.

Cooking was over open fires and firewood had to be collected every day. Bread had to be baked and meals prepared. There were no shops, so you had to spin your own wool and make your own cloth and sew your own clothes and mend your own shoes. You had to look after the vegetables growing in your own garden and if you had animals such hens or a pig, these had to be cared for every day - no days off for livestock farmers!

Click here for Lords of the Manor in the Middle Ages.

Find out about Langar Hall, the Manor House of Langar.

Our Medieval churches

St Andrew's Langar The lost church of St Ethelburga St Mary's Barnstone

Weblinks

↓ There's more - not about Langar and Barnstone, but fascinating information about the East Midlands in the Middle Ages: ● learn about the only open-field village left in England, ● watch a film about medieval farming, ● listen to medieval English.

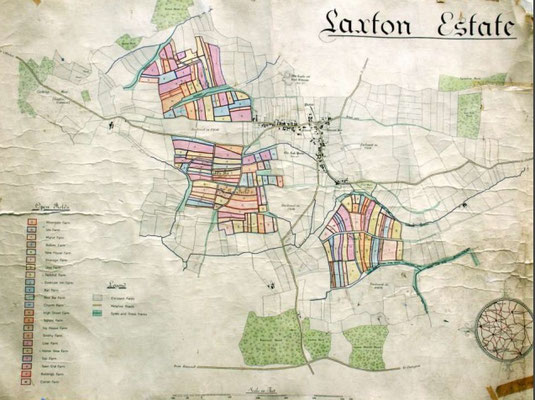

Laxton

10 miles north of Newark is the small village of Laxton, a typical Nottinghamshire country village:

except that it's not at all typical!

Laxton is the only village in England

- in Europe - in the world! -

to still have the open field system where farmers have strips in different fields around the village. Modern farming techniques are used but the ancient system of open fields and strips is still used and protected by law.

↑ Click to enlarge the images of the Laxton open fields.

Watch - You can watch two videos about this remarkable survival:

Medieval Village, an educational film made in 1935 on the British Film Institute website.

and a modern film made by nottstv - Rediscovering Notts: the Medieval Village.

These weblinks take you out of this website.

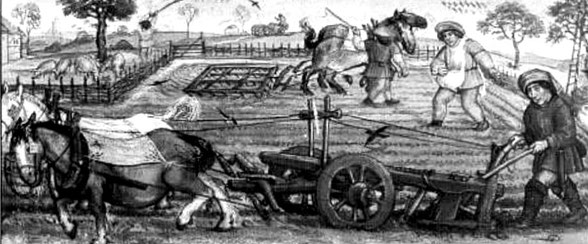

Life on a Medieval Farm: The Luttrell Psalter

The Luttrell Psalter gives you a remarkable glimpse of farming life in the Middle Ages.

The Luttrell Psalter is a book containing the Psalms from the Old Testament of the Bible. It was made in the 14th century for a wealthy Lincolnshire landowner, Sir Geoffrey Luttrell of Irnham. It was copied out by hand, probably by monks in a monastery at Lincoln.

This is the most striking book to survive in England from the Middle Ages - it is richly painted and decorated with silver and gold with detailed illustrations. The Psalter is especially interesting because it shows scenes of everyday life in detail.

But remember: The book was made for a rich man. When you look at pictures of jolly peasants working happily in the fields, this is how the artists thought Sir Geoffrey would like to see them, and not how they really were.

Luttrell Psalter - The Movie

In 2008 Lincolnshire Heritage Film-makers made a film of the Psalter using local people to illustrate the pictures in the book using 14th-century music of the psalms.

Click to watch the Luttrell Psalter film on YouTube.

The weblink takes you out of this website.

What did people sound like in the Middle Ages?

The English language gradually changed from the Old English of the Anglo-Saxons to Middle English which is still not like the English we speak today.

Geoffrey Chaucer was a poet who wrote the story of a group of Christian pilgrims travelling from London to Canterbury Cathedral.

Click to hear the beginning of his 'Canterbury Tales' published in 1387 in Middle English.

The weblink takes you out of this website.