The Georgians - canal mania!

Go back to The Georgians. See also Turnpikes and Cheese and Pies.

Is there a canal at Langar? No!

- but just 2 miles down the road at Harby or 3 miles to Cropwell Bishop

and you'll find the Grantham Canal that was dug over 200 years ago.

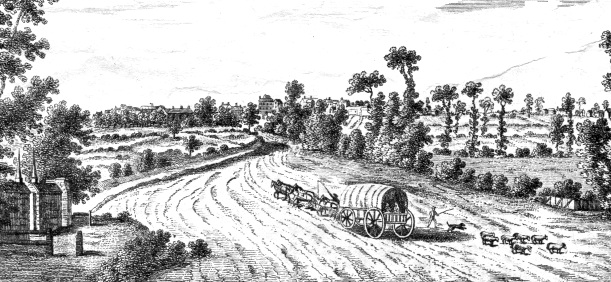

But first . . . road transport in Georgian times

A horse could pull a cart weighing 1000 kilograms (1 tonne) on a normal road, and 2000 kg on a good turnpike road.

(See Georgian Turnpikes for more information.)

Travelling by water - much greater loads

Rivers had been widened and deepened in Britain from Roman times. But in the 18th century changes gathered pace.

- In 1699 an Act of Parliament was passed to improve the River Trent so that boats could travel past Nottingham all the way to Burton-on-Trent.

-

In 1753 Lincoln Corporation improved the Fossdyke Canal to the River Trent.

(That canal may be the oldest man-made waterway in Britain, having been dug by Romans in AD 120.)

Horses and carts could carry much more on the turnpike roads than on the old medieval tracks.

But a boat on a large river such as the River Trent could carry more than 30 tonnes - as much as 30 carts or 300 packhorses.

The Industrial Revolution

Steam engines were used to power factories by the 1760s, Steam engines need large amounts of coal to boil the water to make the steam to make the wheels go round to power the machines.

However, even the turnpikes struggled to cope with increasing quantities of coal and ore and raw materials being used in the industrial cities.

Weblinks

The Industrial Revolution and the Importance of coal

Changes in farming as a result of the Agricultural Revolution had a big impact on Langar and Barnstone and all the villages in the area. There was also a revolution happening in industry - the Industrial Revolution. The main impact of this was seen in the development of larger towns such as Nottingham, Stoke-on-Trent, Birmingham and Manchester. Watch the videos about the Industrial Revolution and the Importance of coal.

The weblinks take you out of this site.

So, if you can move more goods on the rivers than the roads . . .

Good idea!

why not use the rivers for transport?

Problem . . .

The rivers did not always go where people needed them.

For instance, the London Lead Company had lead mines and smelting works near Chesterfield in Derbyshire; and the Duke of Devonshire had an iron smelting works also near Chesterfield. Both needed large amounts of coal and both wanted to transport heavy goods (lead and iron).

- The solution: transport by water.

- The problem: the River Trent was 30 miles away.

If there isn't a river, make one!

One of the first canals to be dug in England since Roman times was the Sankey Canal in Lancashire built in 1757 to carry coal and iron ore 16 miles to the River Mersey and on to Liverpool.

But it was the success of the Duke of Bridgewater's canal in 1761 from his coal mines at Worsley to Manchester which encouraged the greatest interest in canal building. The owners of coalmines and other businesses soon realised how they could profit from moving large amounts of goods to the places they needed them and made plans for their own canals.

The Trent & Mersey Canal was completed in 1766 linking the east and west coasts of England by water. From Nottingham you could now carry goods to Liverpool or Hull and then ship them across the sea.

There was a mania of canal building across the country especially during the last quarter of the 18th century, though canals were still being built up to 1835. By 1840 there were 7000 kilometres of canals in a figure-of-eight linking the seaports of Liverpool, Hull, Bristol and London with Birmingham at the centre.

The Georgians

Canal mania in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire went canal manic. From 1777 to 1797 a new canal opened every four years

Canals here could make use of the River Trent, which cuts right across the county, as a waterway from Burton on Trent to the River Humber and on to the seaport of Hull. The owners of the coalmines in Nottinghamshire could transport large quantities of coal from their mines to towns and factories.

- The Chesterfield Canal 1777

- The Erewash Canal 1779

- The Cromford Canal 1794

- The Nottingham Canal 1796

- The River Trent and Beeston Canal/Beeston Cut 1796

- The Grantham Canal 1797

The Chesterfield Canal 1777 - the first canal built in Nottinghamshire, promoted by the London Lead Company to ship lead from their smelting mill near Chesterfield and the Duke of Devonshire to serve his iron furnace near Chesterfield. Coal, iron, stone and lead were carried to the River Trent; goods carried the other way were grain, malt, timber and lime.

The Erewash Canal 1779 - promoted by the owners of the coalmines in the Erewash valley who wanted to transport their coal to the River Trent and on to Nottingham.

The Cromford Canal 1794

- promoted by the owners of coalmines, iron furnaces, limestone quarries and the cotton mills at Cromford.

The Nottingham Canal 1796

- promoted by the owners of coalmines near Nottingham in competition with the Erewash Canal. Other goods carried were gravel, road stone and manure.

The River Trent and Beeston Canal/Beeston Cut 1796

The Trent has always been an important waterway, but it was not until the late 18th century that improvements were made. Locks were built at Newark and at Holme Pierrepont and the Beeston Canal was dug to make a short cut to the River Trent through Nottingham to avoid tricky conditions on the river near West Bridgford.

In 1794 Robert Lowe wrote about about the great variety of different goods being carried by water in the county of Nottingham: "There is a great trade carried on in this county by water, by means of the River Trent, and the different canals.

-

By the Trent are carried downwards: lead, copper, coals, and salt, from Cheshire, cheese, Staffordshire ware, corn, &c.;

[exports]

upwards, Norway timber, hemp, flax, iron, groceries, malt, corn, flints from Northfleet for the Staffordshire potteries. [imports] -

By canals - downwards: coal, lead, sleetly stone, lime and lime-stone, chirt-stone, for the glass manufactories, coarse earthenware,

cast metal goods and pig metal, oak timber and bark, and sail cloth. Upwards, Fir timber and deals, grain, malt and flour, groceries, bar iron, and Cumberland ore, wines, spirits, and porter,

hemp and flax, cotton-wool and yarn, Westmorland slate, and various sorts of small package.

Upwards and downwards, bricks, tiles, hops, and candlewicks: other articles, however, bear but a small proportion to the coal, downwards; and the corn, groceries, foreign timber, and iron.

The Grantham Canal will supply the Vale of Belvoir with coal and lime - not yet finished."

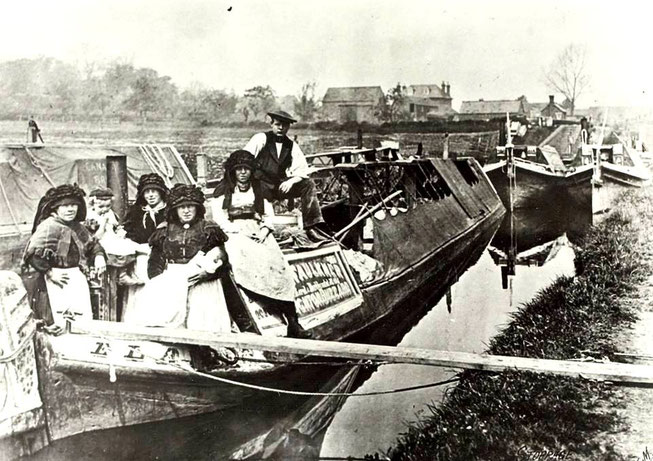

The Grantham Canal 1797

The Grantham Canal was the last major waterway built in Nottinghamshire. Built to carry coal from the Nottinghamshire coalmines to Grantham, the 33-mile long canal (53 km) took four years to build and opened in 1797. Starting at the River Trent near Trent Bridge, Nottingham, it passes through 18 locks and under 69 bridges on its way to Grantham.

The canal ran successfully for 50 years taking coal and building materials to Grantham and bringing back corn, malt, beans, wool and other agricultural produce.

The End . . .

When the railways started to be built from 1837, business on the canals began to decline.

Like the canal boats, railway trains could move large quantities of goods but they were very much quicker than canal boats.

It took more than a week to go from Nottingham to London by boat along the canal travelling at 4 miles per hour. By 1850 the fastest trains travelled at 80 mph - London was just 3 or 4 hours away from Nottingham.

In 1854 the owners sold the canal to the Ambergate, Nottingham, Boston & Eastern Junction Railway when their railway line from Ambergate to Grantham was opened.

Traffic on the Grantham Canal declined as the railway company neglected the canal.

By 1929 there were no boats at all using the Grantham Canal though it was not until 1936 that it was closed.

Water levels had to be kept at 2 feet (60 cm) for the farmers' needs, so the canal still had water in it. However, the locks and bridges were not looked after and, in the 1950s, 46 of the 69 canal bridges were lowered as part of road improvement schemes.

Above left: one of the original hump-backed bridges built about 1797.

Above right: After the canal closed, flat bridges were built which made it impossible for boats to pass.

Across the country some canals were still used to carry goods until after the Second World War (1939-1945), but by the 1960s competition from the railways and the new motorways took most commercial traffic away. By 1970 the 5000 miles of England's canals had been reduced by half.

Many canals were simply abandoned, others were filled in and some were built over.

Above: The wharf of the Grantham Canal at Grantham has been built over as an industrial estate. Image from Google Maps Streetview.

Above: Long stretches of the Grantham Canal have no water and have been turned into footpaths and cycle trails. Left to right: near Cropwell Butler (A46), Cropwell Bishop and Colston Bassett. Photographs from the Geograph website

Above: The Grantham Canal near Stathern where the canal has water and has returned to nature.

Restoration

As early as the 1950s some people realised that we were losing an important historical and leisure asset. Groups were formed to restore disused waterways. In 1970 the Grantham Canal Society was set up and they have been working ever since to restore it.

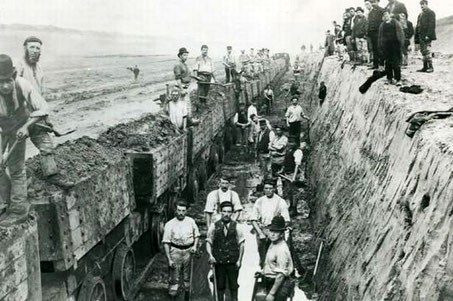

Restoring a lock on the Grantham Canal - not an easy job!

The Society has restored two stretches of the canal for boats to use and some bridges and locks. However, there are problems at both ends of the canal. Access to the River Trent is no longer possible as a road has been built across the canal, and similarly at Grantham.

Fancy a boat ride?

Left and above right: The Three Shires is a short narrow boat that was built specially for the Grantham Canal Society; and you can take a trip on it. Find it at the Dirty Duck Public house at Woolsthorpe by Belvoir.

(Check the Society's website for details.)

It took 4 years to build the Grantham canal from 1793 to 1797.

It has taken 20 years to restore just a part of the canal - from 1970 to the present.

Weblink

A video from the BBC:

The transport revolution - Britain’s canal network

The link takes you out of this website.