The Georgians

1714 - 1837 - largely the 1700s (18th century)

START: Queen Anne, the last of the Stuart family to reign, had no surviving children. Her nearest Stuart relatives were Roman Catholic and barred from being British monarchs. Her protestant 3rd cousin, George, Duke of Hanover, became king in 1714.

Note: The period is named after four kings called George belonging to the House of Hanover. But William IV and Queen Victoria were Hanoverian too. However, William usually counts as Georgian, while Queen Victoria has a period of her own.

END: The death of William IV in 1837 marked the start of the Victorian era.

Georgian monarchs with the dates

they reigned:

George I 1714 - 1727 George II 1727 - 1760

George III 1760 - 1820 George IV 1820 - 1830

William IV 1830 - 1837 (Victoria 1837 - 1901)

Click for Georgian Lords of the Manor, find out about Langar Rectory, the Turnpikes and Canal Mania.

Interested in food? So were the Georgians. Find out about Pies and Cheese.

Revolution!

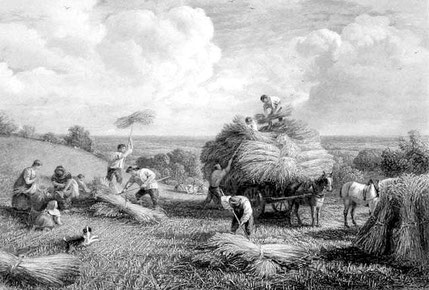

- an Agricultural Revolution

For the 500 years since the Middle Ages farmers worked strips of land scattered around the large open fields of the village. Everyone grew the same crops year after year. The villagers shared the oxen and the plough and they helped each other in the fields. Everyone used the common land to graze their cows and sheep.

Enclosures

Rich lords did not need to share a plough or oxen - they had their own. And they did not want to grow the same crops as everyone else - there were new ideas in farming, And they did not want all their land scattered in strips around the village fields - they wanted it all in one place.

Enclosure meant sharing all the land out out between the people who farmed the strips and putting fences or hedges round the new fields.

Now, everyone's land was in one place and not scattered across the open fields. The common land was also shared out and fenced off. This was sometimes agreed by all the landowners in a parish. Usually it was agreed by the wealthy landowners and the poorer farmers had little choice.

(For more on enclosures, go back to The Stuarts.)

Advantages

- especially for people who owned a lot of land -

- A farmer's land was all in one place - workers did not have to walk miles to their different strips.

- Less land was wasted with tracks between strips and fields.

-

Because the large area of common was now shared, this gave landowners more land to themselves.

- It was easier to control weeds, easier to scare birds from the seeds that had been sown and the crops, easier to keep livestock from straying onto the arable fields.

- Landowners could do whatever they wanted in their fields; they could try new crops and farm machinery. They could keep livestock more easily because the fields were fenced or hedged.

✔

Disadvantages

- especially for people who did not farm much land -

- With the common land gone, there was nowhere for poorer farmers to graze their livestock.

-

When enclosure took place, farmers had to put a fence or hedge around their fields within 6 months. Poorer farmers could not afford this, so they often sold

their land to the richer farmers.

If they were tenants who rented their land, they just gave up their land back to the landlord. - Poorer farmers were not able to share resources as they used to. They could not work together as they used to. Villages lost the strong sense of community they had.

✘

The result was that

medium-sized farms grew bigger,

large farms grew very much bigger,

while small farms gradually disappeared.

Landless farm workers tried to find employment on the larger farms - or they moved to cities such as Nottingham or Leicester to look for work in factories. The number of people living in the countryside began get smaller, the number of people in towns grew larger.

Viscount Scrope Howe

- ahead of the game!

Most enclosures in Nottinghamshire took place in the 18th century. However, Viscount Scrope Howe of Langar Hall had already enclosed Langar in the previous century in 1681. Almost all the land in Langar and Barnstone was owned by him and rented out to other farmers.

(Scrope Howe was always looking for ways to make money - go to Lords of the Manor in Stuart times if you

want to find out more.)

Pastoral farms - keeping livestock

The Vale of Belvoir has rich, fertile clay soil, which grows good crops. However, it is stiff soil, difficult to work especially when wet or very dry. It is easier to pasture livestock (cattle and sheep) on land like this - and much easier in the new hedged fields where the animals could not wander away.

Arable farms - growing crops

Wheat fetched a good price at this time, so although it was more difficult, slower and more expensive to plough and plant, it was worth

it. And there was an increase of 70% in the wheat yield grown in enclosed fields. Barley was also grown and

sold to the breweries in Nottingham to make beer.

Mixed farms - keeping livestock and growing crops

By the end of the 18th century, most parishes in the Vale of Belvoir had farms with a mixture of arable and pasture, crops and animals.

↑ Some things have changed since the 18th century, but the main pattern of the fields

at Langar and Barnstone dates from 1681 when Viscount Howe was lord of the manor.

The rolling English road

Left: Z bends! The rolling English road wiggles and waggles its way through the countryside. It was not designed but developed from tracks that people used to get to work in the fields. This is the road from Langar to Bingham.

Right: Long straight roads like Canal Lane heading towards Stathern were drawn on a map by the surveyors who planned the layout of the enclosed fields in the 18th century. See if you can spot any on this Google map (Takes you out of this website).

This famous poem by G K Chesterton gives a different explanation as to

why English country roads are not straight.

Before the Roman came to Rye or out to Severn strode,

The rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road.

A reeling road, a rolling road, that rambles round the shire,

And after him the parson ran, the sexton and the squire;

A merry road, a mazy road, and such as we did tread

The night we went to Birmingham by way of Beachy Head.

(Extract from 'The Rolling English Road' by G K Chesterton 1913)

Click to find more about the Open field system of the Middle Ages and Enclosures from Stuart times.

New ideas in farming

Landowners began to experiment with different crops. Some Nottinghamshire farmers planted apple and pear orchards; hops were grown (used in beer making). Linen clothes, bedsheets and tablecloths became popular in the 18th century and a plant called flax was grown from which linen is made.

Societies were set up to encourage people to share new ideas. Newark Agricultural Society, formed in 1799, is the third oldest in the country.

The West Riding & Nottinghamshire Society for Encouraging Improvements in Agriculture encouraged new crops and new farming methods. They held competitions for the best livestock, the highest yields of crops, and the best examples of farming techniques.

Prizes were given for carrots, cabbages, potatoes and turnips grown in different types of soil. There were prizes for the farms with the neatest fences, ditches, banks, roads, gates and stiles. The Society believed this would encourage other farmers to do the same.

New methods, new inventions

Jethro Tull

Jethro Tull was a wealthy farmer from Berkshire who thought that scattering seeds by hand was wasteful and inefficient. He built seed-sowing machines and experimented with them; he travelled Europe to see how other people sowed seed. And in 1733 he published a book called:

"Horse-hoeing Husbandry: An Essay on the Principles of Vegetation and Tillage. Designed to Introduce a New Method of Culture; Whereby the Produce of Land Will be Increased, and the Usual Expence Lessened. Together with Accurate Descriptions and Cuts of the Instruments Employed in it." . . . some title!

Jethro Tull believed that horses were better for farm work than oxen. He made drawings of how to make a machine to plant seeds (a seed drill) and a better version of a plough; he had them printed so that anyone could copy them. In experiments with his seed drill, wheat produced a far larger crop than before.

↓ Below: pictures from Jethro Tull's book showing how to make farm machines. Click to enlarge

So why was Jethro Tull's seed drill so good?

Planting seeds had been done for hundreds of years by farm workers walking up and down the fields throwing handfuls of seeds across the ploughed earth.

Problem: the seeds were often scattered unevenly, a lot here, not many there.

Problem: the seeds lay on top of the ground, so many were eaten by birds, some were washed away when it rained, some grew on top of the soil and dried and died in the sun.

Solution: Jethro Tull’s seed drill pushed the seeds down into the earth and planted them evenly across the field. One worker with a seed drill could do the work of many farmhands and do it better!

New methods, new inventions

Turnip Townsend

Viscount Townshend →

Doesn't look much like a farmer, does he ?!

Well, he wasn't.

Charles Townshend, 2nd Viscount Townshend, Knight of the Garter, Privy Councillor, Fellow of the Royal Society was a politician and a government minster - he was the Secretary of State for the Northern Department responsible for British foreign policy in northern Europe. His brother-in-law was the Prime Minister, Robert Walpole.

Doesn't look much like a farmer, does he ?! ↑

Well, he was!

When Charles Townshend retired to his country home in Norfolk in 1730, he spent his time experimenting with different methods of arable farming to see which was the best way to grow crops.

How it used to be done -

The medieval system was to plant one field with barley or beans, a second field with wheat and to leave the third field with nothing growing (fallow) to recover. So only two thirds of the land produced crops each year.

(For more on medieval farming, go back to The Middle Ages.)

Turnip Townshend's new method -

Charles Townshend thought this was wasteful. He tried a four-course system of crop rotation. There would be no fallow field. Instead, four different crops were grown: wheat, turnips, barley, and clover. They were grown in different fields each year.

The two new crops were turnips and clover.

- Turnips were good at keeping weeds down, they could be eaten by people and they could be fed to the cattle which then added manure to the soil.

- Clover added nitrogen to the soil through its roots (good fertiliser).

- No need to leave a field fallow to recover from the previous year's crop. More livestock were kept, soil fertility increased and more food was produced.

Some farmers did more. In 1798 Mr Thoroton Pocklington of Kinoulton (7 miles from Langar), 'an active and spirited farmer', had sixteen crops growing with no fallow field.

New methods, new inventions

Farmer George

King George III was very interested in agriculture and tried out new farming methods on the royal farms at Richmond and Windsor with successful results.

The King visited farms and chatted to local people about farming methods, which gained him popularity and respect. It earned him the nickname 'Farmer George.'

Flood!

Flooding of Stroom Dyke in the 1960s - photos from the Langar cum Barnstone History website

The Vale of Belvoir is a flat, low-lying area. Although the rivers are small, they do flood after heavy rain.

Before the 18th century, when the river valleys were not flooded, they provided lush grass to pasture livestock. But wide areas of land were unusable in autumn, winter and spring after rain.

Most of the Vale of Belvoir was drained in the 18th and 19th centuries and the river-side fields are now often sown with autumn and spring cereal crops. Root crops are sometimes grown although they can be difficult to harvest if the soil is wet.

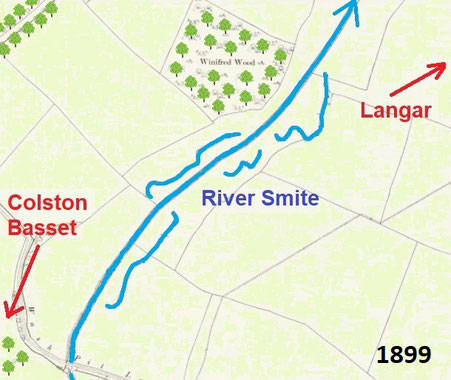

The River Smite and Stroom Dyke are not easy to see now. Look for a row of trees across a field lining the river banks.

Smite is an old Anglo-Saxon word which meant 'a marshy muddy place'.

Stroom meant 'fast flowing'. The word dyke suggests that the stream had been dug out, probably to try to stop it flooding across the fields.

Below: photographs of the River Smite near Colston Basset by Derek Harper on the Geograph website.

← A modern map of the rivers and streams, ditches and dykes around Langar and Barnstone. Many of the ditches were dug when the fields were enclosed after 1681. The rivers were straightened and deepened during the 18th and 19th centuries.

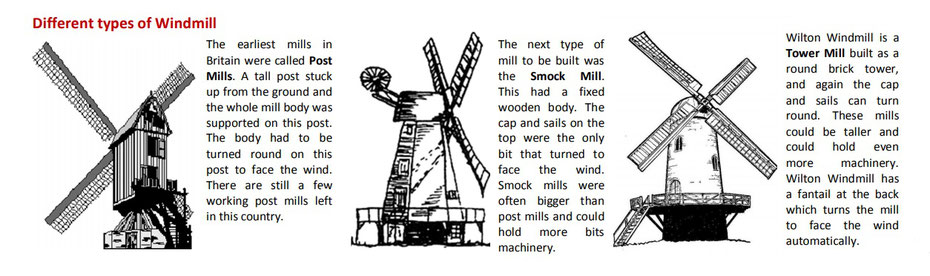

Langar Windmill

Nobody knows when Langar windmill was built. Nobody knows what kind of windmill it was or what it looked like. It was shown on a map of 1818 and was gone by the 1830s. However, you can still the kink in Main Road, Barnstone where it stood - and if you look carefully, you can see the mound it was built on.

Nobody knows who built the windmill, but it was probably one of the Scrope family lords of the manor. They owned most of the land in Langar and Barnstone and they would have been the only ones rich enough to pay for it.

What was Langar windmill used for? Grinding wheat to make flour.

What did Langar windmill look like? Nobody knows,

but it would have been one of these types ↓ probably the first.

Weblinks

There are still a few windmills in Nottinghamshire, though most of them have been converted into houses. But there are two windmills that have been restored and you can visit them to see them working.

These links take you out of this website.

Tuxford windmill is 30 miles north of Langar. Visit their website.

Watch this short Youtube clip

of the sails going round.

Green's windmill is in Nottingham, just 10 miles from Langar. Visit their website.

Watch this YouTube clip

of the windmill grinding corn.

Where did we live in Georgian times?

Until the 18th century people in Langar and Barnstone lived in houses built round a timber frame with the spaces between the wooden posts filled with wattle and daub.

A new fashion - brick

In the 16th century (Tudor times) brick was a fashionable and expensive material. Only the rich could afford houses built of brick.

Holme Pierrepont Hall was the first brick house to be built in Nottinghamshire.

However, by the late 18th century most new village houses were built of brick.

Most people in villages did not own their house in the 18th century; they rented it from the lord of the manor. He repaired the old timber-frame houses for as long as he could. Often the thatched roofs were replaced with tiles.

But when the house was too old to be repaired, the lord of the manor replaced it with a house built of brick. Clay was dug from local pits and the bricks and roof tiles were baked in kilns nearby. There was a brickworks at Cropwell Bishop.

Old!

Some of the large farmhouses in Langar were built in the 17th century but the oldest cottages for ordinary working people are on Church Lane.

They were built at the beginning of the 18th century and were originally a terrace of four cottages. They have now been made into one house called Church Cottage.

Look at the roof . . .

The roof of Church Cottage in Church Lane is covered in clay tiles now. But look at the steep roof. This is a clue that it used to have a thatched roof.

→

Pantiles are light and fairly cheap to make. They are curved to fit together easily and do not need a steep roof like thatch. This makes a cottage cheaper to build.

The houses below were the houses of well-off farmers in Langar and Barnstone.

Click the pictures to enlarge them.

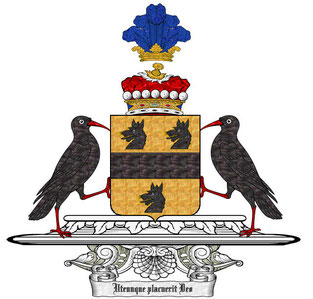

The Unicorn's Head public house

The village inn was originally called 'The Feathers', taking its name from the plume of feathers in the Howe family coat of arms. The Howes were the lords of the manor at Langar Hall. The pub's name was changed to 'The Unicorn's Head' after industrialist John Wright bought the manor in 1818.

In the early hours of 1st September 2015 the Unicorn's Head was badly damaged by fire. The pub was very difficult to rebuild. Everything had to put back in the same way as it had been in 1717. The whole roof and the entire front of the pub was taken off and rebuilt. It took 40 tonnes of lime plaster mixed with goats' hair, £37,000 of oak and countless pieces of wooden dowelling (nails and screws were not used in the 18th century). It was two years before the pub opened again.

Now this isn't nice - crime and punishment

A whipping

On 5th April 1725 John Kettleborough was sentenced at Nottingham to be whipped at Bingham Market Cross.

John Boulton gave evidence that he had been working in Langar Park at the brick kiln there for the Right Hon the Lord Viscount Howe and had used a spade belonging that noble Lord, but on coming to receive his wages at the end of his time the spade was missing. Mr John Doubleday, steward to that noble Lord stopt half a crown [2 shillings and 6 pence] with him for the spade being mist.

A warrant was issued and the spade was found in the possession of John Kettleborough of Great Cropwell, who told the court that he bought it after Bingham Fair Day on the 28 October from John Allen who was working at that time as servitor [assistant] to a mason for the Lord Viscount Howe.

John Kettleborough was found guilty to the value of 10 pence and was ordered to be whipped at the Market Cross in Bingham by the gaoler [jailer].

? Who do you think stole the spade ? Did they whip the right man ?